When Is Anti-Zionism Antisemitic? Getting Beyond the Polemics

Ethan Katz

Ethan Katz is an Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley; faculty director of the Center for Jewish Studies, and co-founder of both the Antisemitism Education Initiative and the Bridging Fellowship dialogue program. His most recent book, co-edited with Elisha Ancselovits and Sergey Dolgopolski, is When Jews Argue: Between the University and the Beit Midrash.

On July 15, 2025, as I sat behind the Chancellor of my university while he testified before the House Committee on Education and Workforce at a Congressional hearing on “Antisemitism in Higher Education,” I was struck by the paradoxical nature of the moment. This hearing, the ninth on the same topic held by the committee since late 2023, seemed a nakedly partisan affair, treating all anti-Zionism as inherently antisemitic. Just weeks before the hearing, the Committee’s chairman, Tim Walberg (R-Minnesota), delivered public remarks at the “March on Washington for Jewish Civil Rights,” where he declared that “in order to fight antisemitism we must understand it,” and derided signs at protests declaring “Anti-Zionism does not equal antisemitism” as peddling a “false narrative.” This rhetoric echoes that of the Trump administration. Since late January 2025, in the name of combating antisemitism, White House statements have condemned all pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses, calling them “pro-jihadist” and their participants “Hamas sympathizers.” The administration has warned that protesters who are resident aliens will be deported and that the “antisemitic campuses” that tolerate them will suffer severe cuts in federal funds. Such labels and threats imply that these activists are not only anti-Zionists but by definition antisemites who support the violent elimination of Israel and its Jewish inhabitants.

And yet, during the same period when many in the federal government have posited a highly problematic 1:1 equivalency between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, using this claim as a cudgel with which to silence pro-Palestinian speech, there has been another, countervailing pattern that is no less disturbing. Hearings like the one I sat in draw their lifeblood not only from an unmistakable rise in antisemitism, but from a growing discourse, situated predominantly on the political left, that demonizes all things and persons associated with Zionism and Israel. This discourse frequently depicts Zionism and Israel as a unique, mortal enemy to be treated with unflinching hostility, and ultimately, eliminated. In the period since October 7, the human toll of this rising discourse has been on regular display in the form of social ostracism, intimidation, harassment, and even violence, particularly against Jews and Jewish communities. College campuses have often been ground zero for these developments—and have thus drawn overly zealous, often bad-faith attention from conservatives in Washington, D.C. It seems clear that sometimes, anti-Zionism is indeed antisemitism.

Two lethal attacks against Jews that occurred far from university campuses this spring showed the seriousness and ubiquity of a dehumanizing strand of anti-Zionism and raised anew the question of the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On May 21, a gunman shot dead two employees of the Israeli embassy in Washington as they left an American Jewish Committee event held at the Capital Jewish Museum. On June 1 in Boulder, Colorado, a man threw Molotov cocktails at a group that had gathered for a run/walk of “Run for Their Lives,” an organization seeking the immediate release of all hostages taken on October 7; several days later, an elderly woman, who was among the dozen or so victims, died from her injuries. In both cases, the perpetrator shouted, “Free Palestine!”

***

What do these seemingly counterposed, yet simultaneous trends tell us about the relationship today between anti-Zionism and antisemitism? Is it actually possible that a series of attacks on Jews, carried out in the name of anti-Zionism, is erasing the line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism; and that simultaneously, a relentless stream of political accusations is falsely equating anti-Zionism and antisemitism?

This paradox grows out of a larger, pre-10/7 impasse in how we understand the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. Attempts to define this relationship have frequently been reduced to bitter polemics between self-identified Zionists and anti-Zionists. What is altogether lost is the much longer history of a complex interplay between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. This overlooked history suggests a paradigm shift in how we might approach these issues today: a move away from a defensive response to anti-Zionism and toward genuine dialogue about Israel, Zionism, the Jewish people, and Palestinian rights—even when it is painful—both within and far beyond the Jewish community. History can, in addition to prompting this paradigm shift, enable us to reassess current fights against antisemitism and delegitimization of Israel by identifying new threats and potential partners we may not have otherwise seen.

Definitions and Distinctions

Terminological precision is crucial to understanding the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. Three major competing definitions of antisemitism have generated tremendous debate and controversy in recent years: the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition (or IHRA, by far the most widely adopted), the NEXUS Document, and the Jerusalem Declaration (sometimes called the JDA). Debates around the three definitions most often center on the matter of where critique of Israel (whether or not it is termed anti-Zionism) intersects with antisemitism. For our purposes here, I will operate according to a relatively straightforward definition of antisemitism that does not make a direct claim about critique of the State of Israel. I draw this definition from my background as a Jewish historian, and from my experience over the past six years helping to lead conversations about antisemitism at UC-Berkeley, in the Association for Jewish Studies, and in numerous other settings across the country:

Antisemitism is discrimination, hatred, or exclusion against Jewish individuals, groups, entities, or institutions, because they are Jewish.

Antisemitism includes attitudes, actions, and structures that impede or condition Jews’ capacity to participate as equals in political, religious, cultural, economic, or social life. Antisemitism shares some important features with other hatreds like anti-Black racism, Islamophobia, or anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination. Yet unlike most exclusionary systems or ideologies, antisemitism very often does not vilify its victims as inferior, but rather as having too much privilege and power.

Across a large chronological and geographical sweep, several antisemitic stereotypes and conspiracy theories have persisted. In particular, Jews have been seen as wealthy or greedy; powerful, controlling puppeteers; cunning and untrustworthy; disloyal to their country or locality in favor of an ultimate loyalty to the Jewish people or Jewish state; and bloodthirsty, violent, and evil.

Though defining antisemitism remains challenging, anti-Zionism is actually far less well-defined. In part, this reflects the complexity of Zionism itself as a historical and contemporary phenomenon. For all its various competing historical strands, most Jews have long seen Zionism as an ideology, a movement, and a set of on-the-ground practices and policies in support of a political entity that allows for Jewish self-determination, collective rights, and security in some portion of Jews’ historical homeland. By contrast, for most Palestinians, Zionism has meant an unceasing history of conquest, displacement, and violence on a wide scale, over many decades. Correspondingly, anti-Zionism tends to mean one thing for those who consider themselves Zionists or have a strong sense of attachment to Israel, and something else for those who consider themselves anti-Zionist or strongly opposed in some way to Israel.

Most Zionists and self-declared supporters of the State of Israel understand anti-Zionism as opposition to the Jewish state in every way, questioning its right to exist, and possibly threatening the lives of its Jewish inhabitants. Some equate Zionism with Judaism, and claim that therefore, axiomatically, being against Zionism means being against Judaism (and Jews) writ large. By contrast, for most anti-Zionists, being anti-Zionist means opposing the oppression of Palestinians, without necessarily offering a particular political program. For many of these anti-Zionists, Zionism has come to stand for a host of other forces they oppose, such as imperialism, racism, oppression, and most recently, genocide. As a result, Zionism and anti-Zionism are frequently employed as symbols in larger battles, rather than in a thoughtful manner for their own sake. Frequently, when we argue about anti-Zionism, we only have the vaguest notion of what we are even arguing about.

If we want to get beyond polemics in the conversation over anti-Zionism and antisemitism, I think we need to keep in mind three major distinctions:

Zionism as an idea vs. Zionism as a lived reality

Critical anti-Zionism vs. negationist anti-Zionism

Intention vs. impact

I’ll say a little bit about each distinction here and then delve deeper.

1. Zionism as an idea vs. Zionism as a lived reality

Typically, anti-Zionists focus either on Zionism as an idea or on Zionism as a lived reality. In the first instance, they do not accept the core ideological tenet of Zionism: that Jews have the right to a sovereign, national home in some part of their ancestral homeland. In the second instance, they oppose the current policies, institutions, and often the entity itself that instantiates that core tenet—the State of Israel. In the latter case, anti-Zionists define Zionism, as Peter Beinart has put it, as “what Israel does.” While for some, opposing “what Israel does” means simply criticizing many of its policies, others see those policies as the all-but-inevitable outcome of the state’s continued existence, and they therefore oppose that as well.

2. Critical anti-Zionism vs. negationist anti-Zionism

This leads us to the second distinction, between two different types of anti-Zionism that I label critical and negationist. The former is fundamentally about critiquing what is wrong, historically or at present, with the way Zionism as an ideology or set of practices has developed and unfolded. Critical anti-Zionism endeavors to focus its attacks on a state (Israel) or a political project (Zionist nation-building), and to insist that these are not attacks on Jews broadly. Critical anti-Zionism can often take the form of specific critiques or proposals for fundamentally reshaping the political order in Israel and Palestine—some of these proposals, even if radical, echo other minority forms of Zionism. By contrast, negationist anti-Zionism rejects the legitimacy of the Zionist project altogether or calls explicitly or implicitly for the elimination of the State of Israel or any state that maintains some form of Jewish self-determination in a part of Israel and Palestine. This type of anti-Zionism is often what some scholars call erasive, as it ignores, downplays, or writes out from history the longstanding Jewish roots in the Land of Israel, the history and ongoing reality of antisemitism, and large parts of the history of Zionism and the State of Israel. In critiquing Israel, negationist anti-Zionism frequently employs anti-Jewish tropes.

3. Intention vs. impact

In many instances, there is a gap between the intentional goals of those most critical of Israel and the effect of their words or actions. Someone can intend to focus a given rhetorical attack squarely on Israel, for instance, while still doing so in a way that has a detrimental impact on Jewish individuals and institutions. At the same time, disparate vantage points, experiences, and ideologies on the part of speakers can lend profoundly different meanings to the same expressions of hostility toward Israel or Zionism. For instance, a Palestinian forced to flee as a refugee in 1948 who says that they “wish Israel did not exist” should hardly be heard as holding the same position as a far-right white nationalist who makes a nearly identical statement. The difference is far from academic: the former may signal opportunities for dialogue and clarification of terms, while the latter likely signals a sharp divide over the most fundamental values that reach well beyond the question of anti-Zionism.

Critical anti-Zionism—A Short History

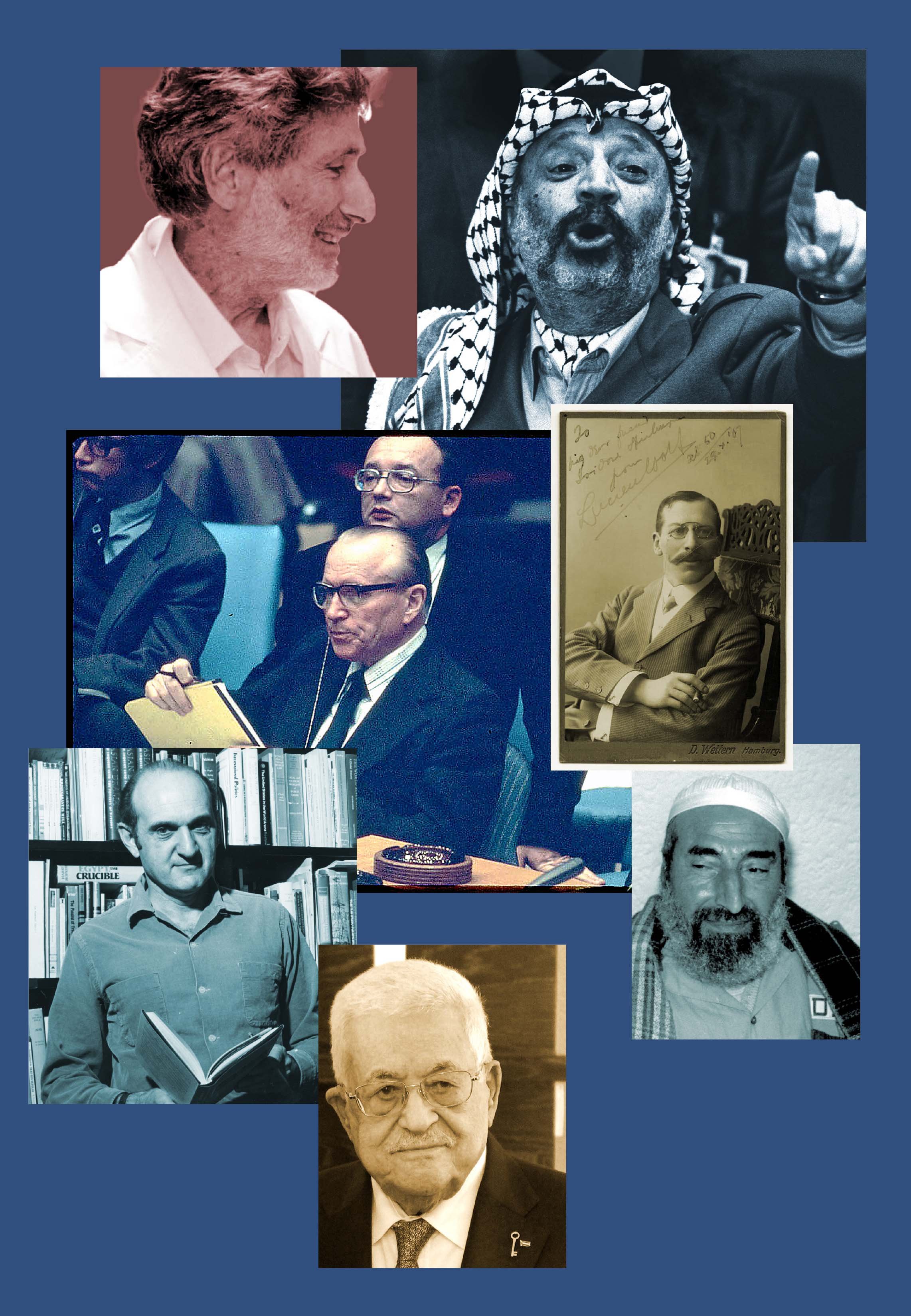

Historically, we find critical anti-Zionism in both Jewish and Palestinian circles. In the decades after the Zionist movement’s founding in 1897, particularly in countries where Jews had attained legal equality and robust levels of social integration, many Jewish leaders spoke openly against Zionism. Critical anti-Zionism expressed by Jews and Jewish groups in the twentieth century tended to come from a vantage point rooted in deep engagement with Jewishness, Jewish community, and Jewish problems. In 1904, Lucien Wolf, a British-Jewish journalist, diplomat, and activist for Jewish rights, published an essay called “The Zionist Peril,” where he called himself “a convinced and uncompromising anti-Zionist.” In addition to lodging numerous critiques against Zionism for its faults, he insisted: “The real Jewish Nationalism, the only true Zion,” is the prophetic goal of “lofty toleration and universalism.” Zionism, for Wolf, was a dead-end ideal that would only provoke increased antisemitism. Today, while ideological differences are often paramount, a similar fear of antisemitism-by-association does seem to be a motivating factor for some Jews at pains to separate themselves from any connection to Israel or Zionism. (Ironically, this mirrors those who insist that all anti-Zionism is antisemitism).

Other 20th-century manifestations of Jewish anti-Zionism were based upon a distinctive vision of Jewish politics quite at odds with the assumptions of Zionism. A variety of Jewish socialist organizations, particularly those connected to Yiddishism, took an entirely different, diasporic approach, and therefore opposed Zionism in a spirited contest for the hearts and minds of the Jewish masses in many countries and locales. Today, those seeking to revive notions of “Diasporism” often express a connection to such historical strands, at times even simply using “Yiddishist” as a virtual synonym—however reductively—for anti-Zionist.

Many Jews active in mainstream Jewish organizations began warming toward Zionism in the years following the 1917 Balfour Declaration. Yet, in the United States and France—today home to the world’s two largest Diaspora Jewish communities—a major shift toward acceptance of Zionism among the mainstream of the community did not begin until the mid-1940s, during World War II. As historian Derek Penslar notes in his recent book Zionism: An Emotional State, before the establishment of Israel in 1948, far more Jews worldwide were avid anti-Zionists than were actively Zionist.

The case of Reform Judaism exemplifies this historical trend. The Reform movement, which started in the mid-nineteenth century, defined Judaism as a religion and saw it as a basis for universalism. It also embraced Jewish acculturation in diaspora societies, and it took a hard line against Zionism, which it saw as antithetical to its positions. In the 1885 “Pittsburgh Platform,” Reform rabbis in the United States declared, “We consider ourselves no longer a nation but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state.” The Reform movement’s 1937 “Columbus Platform” described Zionist efforts in Palestine as “the promise of renewed life for many of our brethren,” which marked the beginning of a shift; in 1942 the movement supported the formation of a Jewish army in Palestine. And yet, even so, it was only in 1977 that the Reform movement declared itself as an organization to be “officially Zionist.”

The most notable anti-Zionist organization in America in the mid-twentieth century, the American Council for Judaism (ACJ), was founded in 1943 as a breakaway from the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), in order to defend and promote “classical Reform’s anti-Zionism.” Its leading figure, Rabbi Elmer Berger, argued that: (1) Judaism had to be sharply distinguished from Zionism, since Judaism is a religion and not a nationalism; (2) Anti-Zionists are, in his words, “neither anti-Jewish nor anti-Semitic,” a statement that was meant to fend off attacks in an era shaped by the memory of the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state; and (3) Zionism is actually antisemitism since, according to Berger and his colleagues, it entails a form of state-sponsored discrimination based upon race and religion against American Jews. Though Berger’s influence in his time was limited, his arguments anticipate ideas expressed by more prominent left-wing anti-Zionist Jews of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, such as Judith Butler and Daniel Boyarin.

As historian Geoffrey Levin shows in Our Palestine Question (2023), though the ACJ’s direct impact was small, it was part of a much wider spectrum of American Jewish critique of Israel in the 1950s and 1960s. Numerous Jews with deep ties to Israel and profound sympathy for Zionism raised fundamental issues that were often—and have continued to be—deemed not only anti-Zionist but antisemitic in their implications. For instance, Don Peretz, the first Middle East specialist on the staff of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), became a leading expert on the Palestinian refugees of 1948, and drafted an initiative for aid to the refugees, which was briefly embraced by the AJC and announced in 1956 at its annual gala. In fact, in large part because of its focus on civil liberties and the way that the organization extended this to the new Jewish state, the AJC remained officially non-Zionist until 1967. Given their commitments to Jewish religion, culture, thought, and/or peoplehood, it is difficult to reasonably judge these thinkers and organizations antisemitic.

Once again, comparisons with the present prove instructive: groups that exhibit these same Jewish commitments today, while fiercely and publicly criticizing the actions of the Israeli government, are few and far between (JStreet and Tru’ah are examples that come to mind, though neither identifies in any way as “anti-Zionist”). Their presence remains part of a lively American Jewish public sphere, and it seems vital to distinguish their commitments from those of organizations that claim the mantle of Jewishness primarily in order to critique Israel or its very existence. Some groups that fall into the latter category, such as Jewish Voice for Peace, can also echo a model of engagement like Berger’s ACJ. Yet three-quarters of a century after the founding of Israel as a Jewish state, Jewish entities that make wholesale rejection of Zionism a centerpiece of their work resonate very differently than they did in the 1940s or even the 1950s. For many Jews, such views are no longer seen as legitimate expressions within the landscape of Jewish politics, but rather as all-out attacks, from “outside the tent,”threatening the legitimacy of a Jewish national project that long ago achieved relative consensus and widespread recognition.

Perhaps surprisingly, there are striking parallels to these Jewish voices among many of the most visible Palestinian Arab critics of Zionism from the movement’s inception to the present. An early expression of this kind of critical anti-Zionism comes in a famous letter from the Palestinian scholar and former mayor of Jerusalem, Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi, to Theodor Herzl in 1899. Al-Khalidi wrote with great respect for both Judaism and Jews, emphasizing their commonalities with Muslims. He condemned the persecution of Jews in Europe and expressed his understanding for the motivations driving Herzl’s nascent movement. Moreover, he declared, “who could contest the right of the Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country!” And yet, he wrote, “Palestine is an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, and more gravely, it is inhabited by others,” who would never assent to being overtaken by newcomers. On the whole, it was “pure folly” for Zionists to plan to take over the territory. Therefore, while “nothing could be more just and equitable” than for “the unhappy Jewish nation” to find refuge, it should be elsewhere. “In the name of God,” he pleaded, “let Palestine be left alone.”

As historians Michelle Campos, Jonathan Gribetz, and others have shown, similar types of critical engagement on the part of Palestinian intellectuals with early Zionists continued during the decades to come. Crucially, these occurred within the framework of Ottoman rule, when it was not clear that the rise of nation-states in the Middle East was in the offing—objecting to the Zionist project in this historical context was part of a larger defense of the empire against a range of ethnic nationalist projects. Equally importantly, such exchanges were often characterized by lively back-and-forth discussion, and by a sense of genuine inquiry and mutual respect, between early Zionist leaders and leaders of the Palestinian Arab community.

This Palestinian Arab strand of critical anti-Zionism continued after the establishment of Israel in 1948. Major Palestinian thinkers of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries who were among Zionism’s most important critics offered explicit recognition of Jewish individual and national rights in Israel/Palestine. In The Question of Palestine (1979), the eminent literary scholar Edward Said starts from the premise that Zionism has only been written about from the standpoint of Jewish history, and not from that of “the Palestinian, for whom … Zionism has appeared to be an uncompromisingly exclusionary, discriminatory, colonialist praxis.” Said pulled no punches, framing his critique of Zionism as part and parcel of his larger critique of Western Orientalism and colonialism.

At the same time, Said felt it urgent to write that no matter the importance of Zionism from the standpoint of its Palestinian victims, “I know as well as any educated Western non-Jew can know, what anti-Semitism has meant for the Jews, especially in this century. Consequently, I can understand the intertwined terror and the exultation out of which Zionism has been nourished, and I think I can at least grasp the meaning of Israel for Jews.” He even went so far as to say, “Zionism has had a large number of successes. There is no doubt in my mind, for example, that most Jews do regard Zionism and Israel as urgently important facts for Jewish life, particularly because of what happened to the Jews in this century. Then too, Israel has some remarkable political and cultural achievements to its credit.”

Said added a new preface for the 1992 edition of The Question of Palestine, writing in the shadow of the then-recent Madrid conference that had brought together Israeli and Palestinian negotiators and set the stage for the Oslo accords. At that moment, he was a supporter of the two-state solution, and he spent much of the preface praising the 1988 decision of the Palestinian leadership to demand a state for Palestinians only in the West Bank and Gaza. Even in 1999, when Said had grown frustrated with the peace process and wrote a piece in the New York Times calling for a one-state solution, he spoke of “self-determination for both peoples,” and floated the idea that in a single state “each group would have the same right to… practice communal life in its own (Jewish or Palestinian) way, perhaps in federated cantons, with a joint capital in Jerusalem, equal access to land and inalienable secular and juridical rights.” However fierce Said’s anti-Zionist stance, he ended up recognizing many of the core tenets of Zionism regarding Jews’ deep attachment to the land, their collective rights as a people, and the need for Jewish safety and security that Israel answers.

Said was not alone among major Palestinian intellectuals of his era, and even today, there are leading Palestinian thinkers, such as the well-known historian Rashid Khalidi, who openly recognize what Zionism has meant for most Jews historically and at present. Sharp opposition to Zionist actions on the ground and/or defense of Palestinian liberation need not mean the rejection of Israel’s legitimacy. Too often, both Jews and Arabs have found their voices silenced as “anti-Zionist” and inter alia antisemitic, when their speech is harsh and derogatory toward Zionism or Israel, but lies firmly in the camp of critical rather than negationist anti-Zionism. Given the uber-polarized dynamics that have developed during the past two years, if we hope to find possible partners for peace or mutual recognition, it is now more important than ever to see these anti-Zionists for what they are: fierce critics of Zionism and Israel who are not driven by hatred or negationist logic, and whose voices should be heard and amplified.

Negationist Anti-Zionism—A Short History

Other strands of anti-Zionism have ventured into more dangerous territory, something I think we should call negationist. By “negationist anti-Zionism,” I mean a total rejection of the claim of Jews to self-determination, and an attack on the Jewish character of Zionism. These sorts of views have been present from Zionism’s earliest days, including from among some of the most pioneering and influential antisemites in history. None other than Wilhelm Marr, who popularized the term “antisemitism” in 1879 as a German political program, wrote at the time of the First Zionist Congress (1897) that “the entire matter is a foul Jewish swindle, in order to divert the attention of the European peoples from the Jewish Problem.” Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg blamed World War I on Jews’ desire to obtain a state in Palestine, while also claiming that the future Jewish state there would, in fact, be “a power base for [Jews’] global, nefarious economic operation.” Such examples—and numerous others—indicate that from the earliest years of Zionism, many antisemites associated the movement with stereotypes about Jewish power, greed, financial control, clannishness, disloyalty, or conspiracy.

This pattern continued in both Soviet and Palestinian Arab anti-Zionism, particularly from the 1960s onward. Historian James Loeffler has traced how the Soviets fashioned and disseminated a distinctive, full-on anti-Zionist ideology in the context of the Cold War and the rise of Third Worldism in the 1960s. More specifically, as Israel became more closely tied to the US and West Germany, the USSR utilized the United Nations and international debates over racism, human rights, and international law as venues in which to denounce Zionism as racism and compare it to Nazism. In 1964, for example, the Soviet representative to the UN delivered a speech that called upon the international community to take action that would lead to the “speedy eradication [of] antisemitism, Zionism, Nazism, neo-Nazism, and all other forms of the policy and ideology of colonialism, national and race hatred and exclusiveness.” Such formulations ultimately helped lead to the infamous 1975 UN General Assembly Resolution 3379 that labeled Zionism as racism.

As Loeffler shows, Soviet propaganda turned on its head Zionism’s original meaning as a movement of liberation from antisemitism, portraying it instead as a movement that allegedly mimicked and benefited from antisemitism. Moreover, in the hands of Soviet propagandists, Zionism and anti-Zionism moved from precise descriptions of specific movements into terms that held broader signifying power for the radical Left—Zionism was linked to globalization and American hegemony, and anti-Zionism represented their opponents. It is striking how strongly this process of inverting anti-Zionism’s significance, broadening its international reach, and unmooring it from real events or people in the Middle East echoes with some of today’s discourse.

Here, distinctions between intention and impact become crucial, for they help us to recognize the significance of the specific vantage point of a given expression of anti-Zionism. There is an important difference between, on the one hand, political ideologues—like the Soviets in the mid-to-late twentieth century, and a certain number of far-left activists today—who have not experienced personal or family suffering at the hands of Zionism, and on the other hand, Palestinians themselves. No matter how strident the language of anti-Zionist negationism from some Palestinians, their opposition to Zionism fundamentally expresses the protest of a people who have suffered personally at the hands of the Israeli state for 75 years. Where you sit, as it were, not only defines where you stand; it also does much to determine its meaning. I can’t help but ask: what if we began our responses to anti-Zionist protests with this basic realization? How might we go about opening conversations if our fundamental disagreements are rooted in sharply divergent life, family, and community experiences, rather than in opposed views of the basic right of Jews to a state of their own? As this writer knows firsthand, such discussions do not unfold easily or comfortably, but they are indeed possible and can often be productive; yet their sine qua non is a willingness to suspend suspicion and fear, and to sit with the discomfort that arises instinctually whenever we hear harsh attacks on Israel’s right to exist—particularly in the current climate.

Negationist anti-Zionism in the writings and propaganda of many Palestinian Arab nationalists emerged alongside the rise of Soviet anti-Zionism. While the 1968 Charter of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) rejected all “discrimination of race, color, language, or religion,” it spoke of Zionism in terms that denied the movement’s origins and validity and demonized its basic character, calling it “racist and fanatic in its nature, aggressive, expansionist, and colonial in its aims, and fascist in its methods.” Moreover, Judaism was described unequivocally as “a religion… not an independent nationality.” The Charter called for the elimination of all Zionism and Zionists from the land of Israel/Palestine. The only Jews welcome to remain in the territory of Israel/Palestine were those who had resided there before 1917, since they were “considered Palestinians.” This was, by implication, not only an erasure of aspects of Judaism and Jewish history, but a call for the elimination of all but a handful of Jews from the land between the river and the sea.

In 1988, the founding Charter of Hamas went a good deal further. It called for “a struggle against the Jews” and dubbed “Israel, Jews, and Judaism” as enemies of “Islam and Muslim people.” Furthermore, invoking classic antisemitic stereotypes, it said that “with their money,” these “enemies” had “formed secret societies,” “control[led] imperialistic countries,” and been responsible for the two World Wars. The charter even cited the infamous antisemitic tract, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, as laying out a factual plan for Zionist territorial expansion that knew no bounds. In 2017, Hamas issued a new set of “Principles and Policies” that pulled back from classic antisemitic language and restricted its critiques to Zionism. Still, it remained unabashedly negationist, as it demonized Israel’s existence, calling Zionism “a racist, aggressive, colonial, and expansionist project based on seizing the properties of others.” Declaring that “the Israeli entity is the plaything of the Zionist project and its base of aggression,” it effectively still implied a Zionist world conspiracy. Hamas’s negationist anti-Zionism reached its zenith on October 7, 2023, as an attack carried out in the name of anti-Zionism manifested openly genocidal intent against the Jewish state and all of its citizens.

On the whole, beginning in the 1960s, many expressions of both Soviet and Palestinian Arab anti-Zionism grew increasingly hostile and even dehumanizing toward all attached to the Zionist project. In the case of the Soviets, and some of their ideological descendants, the anti-Zionism became divorced as well from the specifics of Israel and Palestine. Many Soviet and Palestinian nationalist anti-Zionists took on a negationist logic that dismissed the basic tenets of Zionism and claims to Jewish self-determination in historic Palestine, and they frequently marked their attacks on Zionism and Israel with antisemitic stereotypes.

Our Paradoxical Present

How can this history help us better understand the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism in this current historical moment? More to the point, how can it help provide a basis for effective approaches to taking on these issues today? The paradox with which we began is shaped by two serious threats to the remarkable success story of American Jews: The first is increasing perils to Jewish safety, security, and full expression on many college campuses and in broader communities; typically, attacks come from far-left activists, and they center an increasingly dehumanizing version of anti-Zionism. The second is an assault by many conservatives in Washington on American institutions of higher education—long crucial catalysts for Jewish flourishing in the United States—carried out in the name of combating an antisemitism that is allegedly synonymous with anti-Zionism. Ironically, many of these same right-wing political forces provide cover and even fodder for a more virulent and lethal form of antisemitism among white Christian nationalists, a rising force now for a decade or more in the US and internationally.

The distinctions in this essay can help to sort through this paradoxical situation and move toward a paradigm shift: today, more than ever, American Jews attached to Israel need allies as they seek spaces where they can live out their Jewish identity unimpeded. Those of us who continue to identify in some way as liberal Zionists must find avenues to explain our worldview, our deep sense of connection to Israel, our current concerns, and our need for allyship; and to learn about the perspectives of those who are most critical of Israel, who often understand little about the current outlook of many American Jews.

If we move away from finding anti-Zionism threatening by its very nature, and instead ask about the long-term vision and underlying motivations of the anti-Zionism we encounter, we can find many more opportunities for such critically important conversations. We can find a means for this shift in the three distinctions I have emphasized here: between Zionism as an idea and a set of on-the-ground realities; between anti-Zionism’s intentions and its impacts; and between what I have called “negationist” and “critical” forms of anti-Zionism. In the first instance, those who oppose what Israel does concretely as a state, but not the concept that Jews should have self-determination in a portion of their ancient homeland, are often surprised to know that their sweeping denunciations of Zionism can frequently be read as a denial of the right of Jews to live in their own state. We would do well to ask the question directly: how do those attacking or defending Zionism in these debates define “Zionism”? If the anti-Zionist sees Zionism as the assertion of Jewish self-determination in some portion of Jews’ historic homeland of Israel or Palestine and is against that very idea, that is quite different from opposing the violence and dispossession that Zionism has meant for most Palestinians—a pattern that has, objectively, accelerated to an unprecedented level of death and destruction since 10/7/2023. Dismissing every case of a “Saidian” anti-Zionism as the expression of a “Hamasnic” anti-Zionism closes numerous doors to conversation, implicitly exhibits a startling lack of empathy for Palestinian civilians, muddies efforts to call out real threats to Jewish safety, and can even make Jews less safe.

Those who see Israel as having veered wildly off course and as posing an existential threat to Palestinian life, but who never intend to attack Jews qua Jews, might surprise us if given the chance to share their grievances; then, they might also be more ready to listen to our own fears and frustrations. In a context where we hear out their concerns, we could push them to reflect upon particular slogans, images, and tactics that seem threatening to many Jews; simultaneously, they might give us reasons to reflect on some of our own rhetoric and how it lands for those most pained and appalled by the terrible humanitarian toll in Gaza and the West Bank since 10/7 (and in many respects, for much longer). Likewise, if we assume that hatred is not the primary motivator for those who have encouraged a kind of anti-Zionism that ultimately demonizes Jews, we might find the opportunity to explain why the impact on Jewish life of such demonization can be quite damaging. Assuming their worst intentions means we will never have that conversation, and it only breeds greater mutual resentment and apprehension.

Finally, we need to internalize and articulate the importance of a critical/negationist divide. There are many today who call themselves “anti-Zionist” because they oppose what Israel’s government has become, but they are open to various possible political arrangements that would enable Jews and Palestinians both to live freely as individuals and peoples in some part of the land. Protesters like this have effectively joined a long tradition of critical anti-Zionism that focuses its ire on the policies of the Israeli state, and in the present context, on the necessity of stopping violence against Palestinian civilians. Calls for Palestinian freedom, or for a ceasefire, do not in and of themselves negate the entire Israeli state or the Zionist project, nor are they by definition antisemitic. Listening carefully to the words and demands of protesters can enable us to hear where they are or are not defending the violence of October 7, generalizing about all Zionists or Israelis, utilizing antisemitic stereotypes, or putting forth a political program that calls for an end to the Jewish state—in many instances, they are doing none of these things. At the same time, there have been all too many expressions of opposition to Israel and Zionism that demonize anyone or anything positively associated with the Zionist project, or that glorify “the martyrs” of October 7, or that treat all forms of violent “resistance” against Israeli civilians as “justified.” Such expressions have helped open the door not only to social ostracism, harassment, and discrimination against many Jews, but also to calls for violence and acts of violence. These are classic cases of negationist anti-Zionism, and they are frequently antisemitic—in their rhetorical implications, their impact, or both. It is crucial to identify these cases and to call out precisely their dehumanization and their erasure vis-à-vis the history of Zionism and Israel; it can prove helpful to ourselves and our interlocutors. If we begin from this basic understanding, then we may be surprised to find that there is frequently room to speak with those who call themselves “anti-Zionist” and even to seek common ground.

And such common ground is needed if we are to tackle the very real dangers we face. To be sure, this includes some cases when anti-Zionism itself constitutes a major threat to Jewish safety and thriving. Increasingly, however, the greater threat to both Jews and non-Jews is posed by attempts to quash all expressions characterized as anti-Zionist or antisemitic. As I write this, American democracy faces threats it has not witnessed since the mid-twentieth century: the federal government is moving actively to silence or control speech in numerous contexts, is targeting universities as bastions of free inquiry, and is supported by significant numbers of Americans who do not accept the legacies of the Civil Rights movement as a form of historical progress and see Jews as a threat to white Christian hegemony. If liberal Zionists are to maintain not only our Zionism but also our liberalism, we must take all of these dangers seriously, and we must look for conversation partners and allies in the fight—even in the most uncomfortable and unconventional of places.