American Antizionism

Shaul Kelner

Shaul Kelner is a professor of Jewish studies and sociology at Vanderbilt University and author of the National Jewish Book Award-winning A Cold War Exodus: How American Activists Mobilized to Free Soviet Jews.

A year after the Six Day War, the French scholar Leon Poliakov published the penultimate volume of his magnum opus, a millennia-spanning four-part history of antisemitism. He concluded Volume 3, From Voltaire to Wagner, with the declaration, “Historians are not prophets, and I will refrain, finally, from making any prognosis. Only the future will show if, and to what degree, a hatred of the Jews, justified theologically until the French Revolution and ‘racially’ until the Hitlerite holocaust, will have a third incarnation under a new ‘anti-Zionist’ guise.”

Poliakov did not refrain for long, perhaps because the future showed itself more quickly than he had anticipated. Before turning to the final volume, which carried the history of antisemitism through the rise of Nazism, he rendered his prognosis on the Jewish question of his own day. “[T]he devil painted on the wall has swapped his name from ‘Jewish conspiracy’ to ‘Zionist conspiracy,’” Poliakov wrote in a 1969 monograph. The title of that book, De l’antisionisme à l’antisemitisme, telegraphed the argument. “Under the pretext of a critical attitude toward the Jewish state and its supporters, an ancient passion inspired by hatred continues to make its way.” A meticulous historian, Poliakov then added a nuance that current debates over antizionism routinely ignore: “However, it does so in different ways, depending on the region and the regime.”

Two years after Hamas’s “Al-Aqsa Flood” (we must confront the name for reasons that I will explain below), it is less the horrors perpetrated on October 7 than the traumas of October 8 that have forced an American Jewish reckoning. What does it mean that, of all places, America’s campuses and cities were the most likely to meet Jews in their grief with rationalizations, exhilaration, silence, abandonment, and shunning? Jews in the United States are now discovering how antizionism makes its way here in this region. The experience has caught them intellectually, emotionally, and politically unprepared. I am neither a pastor nor a politician, so I cannot offer much on the latter two. But to those hoping to gain some intellectual footing, I can offer my perspective as a sociologist who has written on social movement activism, a historian who has studied antizionism in the USSR, and a professor who has been navigating academic antizionism in the US since the 1990s. These shape how I understand what American antizionism is, how educational failures enabled it to gain a foothold, how it has become more dangerous (at least for now) than race-based antisemitism, and how Jewish Americans might begin to blaze a path forward.

An American Mass Movement in Action

Unlike antizionism’s Soviet and Iranian variants, no national authority in the United States leads the charge. Rather, coordinated by activist networks, American antizionism has been advancing through petty regimes, to borrow Poliakov’s term—the scholarly association, the student union, the publishing house, the school board, the grocery co-op, the city council, and now perhaps even the mayor’s office. Efforts to institutionalize antizionism via divestment resolutions and boycott policies manifest sporadically at the local level rather than via a unified national policy. This devolution to local government and civil society might be the crucial adaptation in the Americanization of antizionism. It has allowed a new reality to take root without much notice: A mass movement premised on denying and undoing political rights that Jews have already secured now expresses itself through (some) governmental institutions in the United States.

This is new for the vast majority of American Jews, certainly for those born here after World War II. It is not a coincidence that the first book devoted to the critical analysis of antizionism—Poliakov’s—did not emerge from the United States, but from Europe. There, “Jewish questions” have long served as an organizing principle of political debate. Here, on the other hand, the notion of a mass political movement challenging Jewish claims to equality was assumed to be a relic of the past. It was also assumed to follow a specific model: that of Father Coughlin, Charles Lindbergh, the Ku Klux Klan, and the like, i.e, a challenge to individual Jewish civic rights in the US based on religious and racial claims. Nothing in recent American experience prepared Jews for a young and energetic mass movement committed—not for racial reasons but ostensibly for reasons of social justice—to the notion that the principles of equal rights and self-determination of peoples enshrined in the UN Charter should no longer apply to Jews. Had the movement confined itself to critique of Israeli policy, even scathing critique, Jews might have better retained their footing. But the mobilization of antizionism framed itself in the language of opposition to “Zionism” writ large. It is not merely the exercise of Israeli state power that a growing portion of the American public has deemed problematic, but Jews’ claim to have a national right to self-determination in the first place.

How are we to make sense of the rise of such an antagonistic politics in the United States? Having been immersed for more than a decade in the study of Jewish American mass mobilization (specifically, their fight against Soviet antizionism), my understanding is shaped by a vibrant field of sociological scholarship on social movements. This leads me to see American antizionism as a politics that is defined more by its actions than by its arguments. And because I recognize it as an independent phenomenon in its own right, rather than just as a critique of something else, I spell it “antizionism” and not “anti-Zionism.”

These points demand clarification.

First, what defines antizionism better: its actions or its arguments? College-educated people are often guilty of a double standard, viewing working-class political movements as irrationally passionate, but their own political movements as staunchly principled. Because antizionist politics have taken root mainly among the intelligentsia—professors, university students, journalists, artists—many people assume that antizionism is therefore best understood as a reasoned intellectual position, more rational than emotional. This certainly serves the interests of antizionism’s proponents, but it is a fiction rooted in social class biases. Antizionism is like any other political movement. It is not reducible to its intellectual dimensions. In the real world, mass movements are always more than the manifestos proffered by their most articulate spokespeople.

To understand what antizionism is in practice, we should focus less on what its intellectuals say and more on what its activists do. For one, while there may be continuities between what elites express and what the masses enact, there are also always gaps. And it is in these gaps that the protestors seize control of their movement from the writers. But even more important, only through action does a social movement create a reality of its own out there in the world. Our ancestors had a way of saying this: Naaseh v’nishma, “We will do and we will understand.” Behavior comes first. Meanings emerge through the doing. Praxis. This is the social movement not on paper, but in real life.

Look at images from the “mostly peaceful” (i.e., sometimes violent) antizionist encampments that were shared on social media or broadcast on the nightly news. Keffiyeh- and medical-masked demonstrators pitch tents, wave flags, chant slogans, block walkways, storm libraries, and confront Jews. The protests are full of action, emotion, conflict, noise, and drama. The antizionist movement in the US has praxis in abundance. Indeed, the movement’s undeniable success at mass mobilization brings us to the second point: there is a reason it is more appropriate to write of the movement using the spelling “antizionism” in all lowercase without a hyphen.

Consider the alternative. To write of what we have seen since October 8, 2023 as “anti-Zionism” suggests all that is at stake is reasoned critique of the ideologies of Berl Katznelson, Moshe Leib Lilienblum, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, and other formative thinkers who laid the intellectual groundwork for the Jewish state. Such a narrow idealist approach obscures the antizionist movement’s praxis and conceals its scope. Antizionism is more than just a critique. It is bigger than just a set of ideas. One need not agree with it or support it to give it the credit it is due: Antizionism is a world-altering political phenomenon. Every Jew who has felt even the smallest bit affected by the changed political context in which they now live—be it choosing to tuck in a Magen David necklace, deciding not to mention one’s travel to Israel, second-guessing whether to apply to a certain university, or, alternatively, seeking out Jewish community for the first time—can attest to that fact.

Antizionism is also not the first political movement to present itself as an antithesis to an imagined Jewish villain. Decades ago, scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century race-based oppression of Jews recognized that this was true of the politics that they studied. This insight led them to revise how they spelled the name of these politics, from “anti-Semitism” to “antisemitism.” Through this change, they also avoided lending their support to any claims the self-professed “antis” made about “Semites” or “Semitism.” These were properly understood as a phantasmagoria conjured by the antisemite, a socially constructed Other to define oneself against.

Deleting a hyphen is a small move, but it makes a bold claim. Antisemitism has little to do with “Semites” and everything to do with antisemites. It is a phenomenon in its own right, propelled by its own dynamics. To understand it, one has to look at those who profess it rather than those whom they profess to be against. I make the shift here from “anti-Zionism” to “antizionism” for the same reasons.

The antizionism that actually exists out there on American streets is a phenomenon sui generis. It is a political mass movement defined not by abstract ideas but by lived praxis. There is a loose connection between what antizionist professors in the classrooms write and what antizionist students in the encampments do. But the behaviors create a lived antizionism that outstrips systematized ideologies formulated by intellectuals.

In other words, antizionism is what antizionism does. Defined by its practice rather than by any claims it makes about “Zionism,” American antizionism involves a now-familiar behavioral repertoire: encampments and other occupations of university spaces, boycotts of Israeli scholars and artists and also of select American Jewish groups including Hillel and the Anti-Defamation League, masked harassment of Jewish students, defacement and destruction of Jewish property, disruption of performances by Jewish musicians, and so forth. Like other movements, antizionism at the extreme finds expression in political violence: Jews and Israelis in the United States have fallen victim to antizionist physical assault, firebombing, and shooting. Although the violence has been committed specifically in the name of the movement’s professed ideals, it is better understood not as an agreed-upon tool in American antizionism’s strategic repertoire, but rather as an indication of antizionism’s success in constructing an enemy. Those in its ranks who are motivated to take up violence know whom to target.

Antizionist praxis in the US also involves rituals, symbols, and behaviors that build and sustain community. I’ll offer a few examples. Protesters do not simply shout “Free Palestine.” They often add a second “free.” Why? Because the spondee (“Frée, Frée”) followed by the dactyl (“Pálēstīne”) creates a rhythm more easily and mellifluously chanted by crowds. This formulation has become so ritualized within antizionist movement culture that the gunman who murdered Israeli embassy staffers Sarah Lynn Milgrim, z”l, and Yaron Lischinsky, z”l, at the Capital Jewish Museum in May 2025 shouted “Free, Free Palestine,” with the doubled “Free,” as he was being arrested, even though he was alone and even though one “free” would have sufficed to communicate the motive for the attack. He was signaling that his actions were part of a larger antizionist movement.

Boycotting Israel is another example of a behavior that adherents use to demonstrate affiliation with the movement. When someone associates their name with a boycott effort by signing a public petition, for example, they realize antizionism in a behavioral sense. This is also true when they follow through on their commitment, as when a professor refuses to write a letter of recommendation for a student seeking to study abroad in Israel, or when a member of a film festival committee votes to reject a submission because it comes from Tel Aviv. But I would argue that the public declaration of joining a boycott campaign accomplishes something different, and arguably bigger, than the private act of boycotting. Its very visibility makes it a form of collective action. By speaking out in favor of boycotting, antizionists build community, define an Other, and affirm their shared values of excluding and marginalizing that Other.

Of course, those who advocate for a boycott would be loath to speak of the practice in this way. People like to think the best of themselves. Also, acknowledging the thirst to ostracize could make it harder to recruit supporters, particularly in communities that profess inclusion and belonging as core values. Instead, pro-boycott discourse combines moralistic language with statements emphasizing a strategic goal. Boycotts are typically framed as a means to achieve various Israel-Palestine-related outcomes. But as sociologist Robert Merton famously taught, regardless of whether social behaviors fulfill their officially declared “manifest” purposes, they usually also serve some “latent” functions that their practitioners may not be aware of—or are aware of but may not wish to examine too closely. And so it is no great stretch for the sociologically minded to recognize that the antizionist practice of boycott holds far richer and more complex meanings beyond placing pressure on Israel.

The discipline of anthropology holds other keys to deciphering deeper meanings of the practice of boycott. The discipline starts from the premise that the meanings embedded in human behavior are always layered and multidimensional. Boycott campaigns are no exception. And because boycotts, by their nature, center on a refusal to interact, anthropological studies of how and why people police boundaries between Self and Other, between good and bad, become especially helpful. I see the boycotts as a perfect example of what Mary Douglas highlights in her classic “analysis of the concept of pollution and taboo”—the human penchant for dividing the world into opposing categories of purity and defilement. Antizionists establish themselves as a moral community by defining “Zionism” as a polluted category and then practicing rituals of distancing and exclusion. This is the latent meaning encoded in the act of signing one’s name to a boycott campaign or holding a referendum on an institutional boycott. These are behaviors by which antizionists construct themselves as a moral community in contradistinction to a polluting Other. (A polluting Other that, we need not add, just happens to be Jewish.)

I recognize the irony of looking to anthropology to make sense of antizionist praxis, considering that the American Anthropological Association has played an important role in the normalization of antizionism in American academia. Future historians of antizionism will undoubtedly debate whether those leading the successful boycott campaign in the AAA failed to recognize that they were participating in a ritualized Othering, or whether they understood this only too well and used their expertise to more effectively isolate Israelis and Jews. Regardless, the failings of a scholarly association do not negate the insights of a discipline or the window that anthropology gives us onto the nature of antizionism as it exists in the US today.

As I write this, a fragile ceasefire has taken shape in Gaza. Fighting in Lebanon has subsided. The Iranian front is quiet. Let us hope this augurs better days to come. But if American Jews imagine that all this will halt the momentum of antizionism here at home, they misunderstand the dynamics of social movement mobilization. Movements make themselves sustainable by creating a subculture and by building community. In these regards, 2024 was a watershed year for the antizionist movement in the United States. American Jews have hardly begun to recognize this, much less come to terms with it.

Rhetorics of Violence

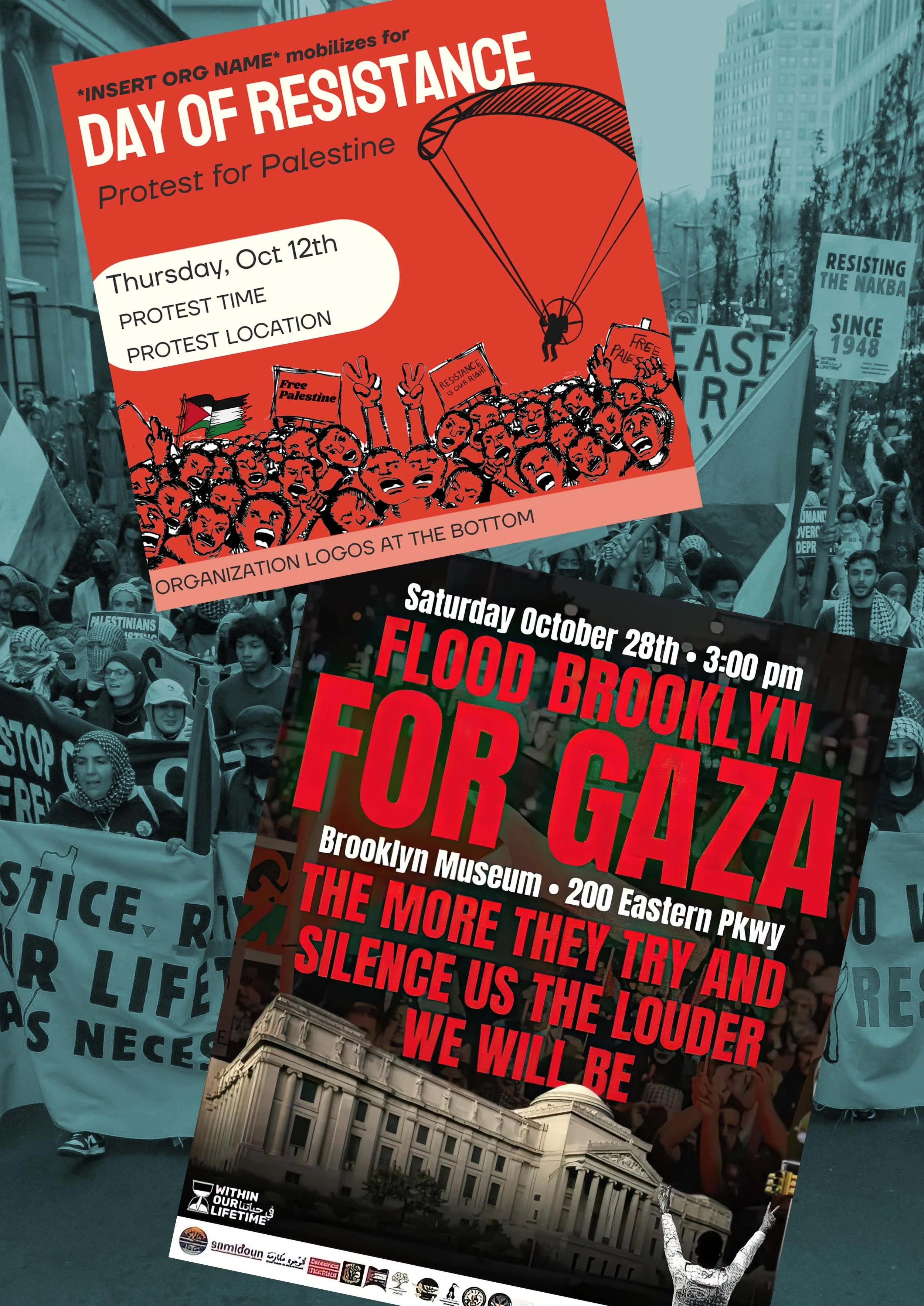

Like their counterparts in Israel, American Jews were caught by surprise on October 7, 2023. They had experienced horror upon seeing the images of slaughter that launched the Al Aqsa Flood. They expected that horror to be shared. In most cases, it was. But American Jews also discovered to their dismay that antizionists in the United States immediately brought the language of deluge into their own communities as a way of symbolically participating in the assault. Just as Hamas was “flooding” Israel, antizionists organized and promoted protests by describing them as attempts to “flood” campuses and streets. For those hoping for a denunciation of the attacks, this was worse than silence. Identity of language asserted identity of purpose, collapsing the distance between the Al-Nukhba Force and antizionist demonstrators an ocean away.

Flood language also enabled antizionists to intimidate American Jews without making the threat explicit. This is part of a broader phenomenon in which would-be tormentors transform elements of murders past into symbols that evoke trauma in the present. Racists wave nooses at Black Americans to evoke lynchings. Antisemites make hissing sounds at Jews to evoke gas chambers. By adopting “flood” language and images of Hamas paragliders even as the victims in Israel were still being tallied, antizionists in the US found a way of supporting the Hamas attacks overseas while simultaneously inflicting emotional pain on Jews here at home. Since October 7, flood language has continued to play a subtle but important role in the expansion and evolution of the Al-Aqsa Flood as a globalized antizionist campaign seeding violence against Jews on every continent.

In the US, as tens of thousands responded affirmatively and “flooded” college campuses, the language of deluge gave way to similarly evocative calls for “intifada.” It is doubtful that most of those adopting the movement’s rhetoric understood the range of meanings of the words activists were inserting into the mobilization. This polysemy proved an asset to the antizionist cause, enabling it to popularize a coded yet plausibly deniable rhetoric of violence. That such rhetoric found fertile ground in universities, where humanities and social sciences faculty typically demand sensitivity to the nuances of language, is one of the more disheartening aspects of the embrace of antizionism within the academy. It is not clear whether this stems from students’ and professors’ readiness to tolerate a coded language of violence or an inability to recognize it. Either way, whether due to moral failure, intellectual failure, or some combination, the result does not reflect well on the American academy.

American Jews, sensing the implications all too well, found themselves flummoxed. How could so many people, and especially young, educated, high-minded Americans, respond so enthusiastically to these calls to “flood” the streets and “globalize the intifada”? Hadn’t Jewish groups invested millions over many decades trying to teach America’s youth that good people shouldn’t join crowds engaging in hostile rhetoric or behavior toward Jews or, for that matter, treating any group as a villainous Other? American Jews had been true believers in the idea that teaching the horrors of the European past could help build a more tolerant American future. Had Holocaust education let them down?

The Problem with a Sample of One

Until his death at the age of 95, Northwestern University professor Howard Becker was one of America’s most original sociologists. Almost thirty years ago, he wrote a delightful book about sociological research methods, Tricks of the Trade: How to Think About Your Research While Doing It. It remains in print today. I give it to graduate students, and I assign it in my undergraduate sociological methods seminar. Unlike most social science methods texts, Becker’s says little about t-tests and statistical significance. Instead, it delivers on its promise and teaches readers how to think.

Becker opens his discussion of sampling by explaining that “every scientific enterprise tries to find out something that will apply to everything of a certain kind by studying a few examples” from which we hope to generalize. But this is often problematic because “the part may not represent the whole as we would like to think it does.” In trying to understand why, he zeroes in on implicit biases that encourage people to limit their investigations to canonical cases while ignoring the rest. Telling the story of his choice to conduct research on medical education at the University of Kansas, Becker related that colleagues could not understand why in the world he did not focus on the Ivies. They thought, he said, that “perhaps we didn’t know any better.” He also told of American Sociological Association president Everett Hughes’s criticism of research into sexual deviance that examined prostitution while ignoring the celibacy of priests and nuns. Why assume that deviation from the norm is found only on the bell curve’s right tail? The distribution also has a tail to the left.

When we impose arbitrary constraints on the samples we choose to consider, we guarantee that we will fail to comprehend the full breadth of the phenomena we want to make sense of. As Becker explains, “Our general ideas always reflect the selection of cases from the universe of cases that might have been considered.” Our knowledge cannot incorporate data from cases we never bother to look at. How is our understanding of the world compromised as a result?

Becker’s book helps us to see one major reason why American antizionism has been tolerated and allowed to flourish. For the vast majority of Americans, including Jewish Americans, what they have learned about the Othering of Jews relies on a sample of one. For half a century, students in American middle schools and high schools have been given a single example of mass anti-Jewish politics over and over, to the exclusion of all else: Nazi-style race-based antisemitism. The decades-long oppression of Soviet Jews in the name of antizionism, to cite another example, is not taught. In American civics curricula and thus in American general knowledge, it might as well not exist.

What is the result? Americans do not have a conceptual language for thinking about the Othering of Jews in all its many flavors. Everything gets forced into the language of “antisemitism,” with its Nazi and racist referents. This has allowed both antizionists and the Jews who fight back against them to avoid engaging with the realities of their own situation. Among the protestors in the Palestine encampments, good-hearted people were prepared to participate in language and behaviors that threatened Jews, and to do so without moral qualms, because they understood their politics as “not antisemitic,” by definition. Why? Because they had been taught that antisemitism is the politics of right-wing racists, and the encampments expressed the politics of progressive anti-racists.

For their part, American Jews frightened or appalled by the protests rushed to label them “antisemitic,” as if this gave them a stronger grasp on the phenomenon. They would have done better to simply note that in these instances Americans were ostracizing Jews in the name of and in the tradition of antizionism—a mode of antagonistic politics rooted in Jews’ Soviet and Middle Eastern experiences, and justified in language originating in Marxist, anti-Western-imperialist, and Islamist ideologies. Had the long and problematic history of antizionism been given even a fraction of the time devoted to Nazi antisemitism in our curricula, museum exhibitions, and Oscar-winning films, Americans would not be limited to a sample of one on which to base their understandings of how political movements define Jews as an enemy. But for motivations we can only ponder, they were given just one historical case to reason with. As a result, public conversation has been shunted down the dead end of debating whether antizionism “is” or “is not” antisemitism. It is not. In the Soviet context for certain, and arguably in the American context today, antizionism is worse.

How is antizionism worse? The Soviet persecutions speak for themselves. The Kremlin declared that its policy toward Jews was rooted in antizionism, not antisemitism. We take it at its word. The American case requires some explanation.

First, consider the likelihood of exposure to day-to-day experiences of marginalization. American antizionism finds its social base in the same educated, urbanized professional class that most Jewish Americans inhabit. Jews are more likely to personally encounter antizionism in their workplaces, schools, and communities than they are to encounter racist antisemitism, whose adherents are mainly drawn from demographics that Jews interact with less regularly.

Second, thanks to the educational system’s sample of one, Jewish Americans know as little about the history of antizionism as do their non-Jewish peers. Ignorant of even the most rudimentary facts about the long twentieth-century tradition of antizionist persecutions, marginalization, and violence, young Jewish Americans possess for antizionism neither the historical awareness, nor the intellectual defenses, nor the visceral repulsion that they have for racist antisemitism. This has allowed antizionists to enjoy some measure of success in recruiting Jewish American support. Obviously, for the movement, the ability to place Jews front and center is a strategic asset, and one that American antizionism enjoys, but American antisemitism does not.

Third, because antizionism comes with a seal of approval from its scholarly supporters, it enjoys a legitimacy that Jewish Americans’ educated peers are reluctant to bestow upon racist antisemitism. (This partly explains the mantra, “I am not antisemitic, I am only antizionist,” as well as why the reverse is not heard: “I am not antizionist, I am only antisemitic.” Class bias is operating here. Among professionals, politics that appear intellectually unserious tend to be stigmatized.) Intellectual legitimacy is an especially important resource as antizionist activists seek to make their movement sustainable. It is a crucial piece of efforts to incorporate antizionism into teacher training and school curricula, shaping how future generations understand their world and the role of Jews in it.

Fourth, because of its particular combination of characteristics—an intellectually justified, socially acceptable Othering of Jews whose social base is in the professional class—antizionism easily makes the leap from individuals’ personal politics to systemic discrimination in the sectors of the American economy where antizionists (and Jews) typically work, shop, and play. One can reasonably speak of institutionalized antizionism in the academy, the non-profit sector, and the arts world. One cannot say the same of antisemitism from the racist right, at least not at the moment.

Only regarding the issue of physical violence can one make a case that racist antisemitism at present constitutes a greater immediate threat to Jewish American well-being than antizionism. Antisemites are better armed, have better paramilitary organization, and are more organized into antigovernmental revolutionary cells. This does not mean that antisemites have a monopoly on violence targeting American Jews, however. The antizionist attacks of Spring 2025 that killed one in Colorado and two in Washington, DC, should disabuse any who comfort themselves with that illusion.

All of this can change. America’s political situation is at its most volatile since the late 1960s. Racist antisemitism is making headway among some factions of the MAGA right. It is possible that such antisemitism will one day supplant antizionism as the primary driver of efforts to roll back Jewish political participation and equality. But at least for now, antizionism’s grip on that role appears secure.

Cognitive Liberation

American Jews are caught in a trap partly of their own making. But I see a few ways out. The paths all begin in the same way, with Jews learning to recognize and name the power dynamics that have rendered them vulnerable in the first place. Cognitive liberation is the prerequisite to any effective response to the degradations of antizionism.

Most importantly, Jews should stop indulging the definitional debate, “Is antizionism antisemitism?” When it is forced upon them, let them simply respond, “Antisemitism is the Othering of Jews from the American right. Antizionism is the Othering of Jews from the American left. All the rest is commentary. Now go and fight both.” If pressed to elaborate, they can remind themselves and those they are addressing that antisemitism and antizionism were state policies of the twentieth century’s two most powerful totalitarian regimes, and that America’s declarations of victory over Nazism and Communism were premature. The legacies of Hitlerite antisemitism and Stalinist antizionism echo into the present day, influencing the thinking of many Americans who are often unaware of the pedigree of their ideas.

Ultimately, it is up to antisemites and antizionists to change their own minds by beginning to understand the history they are perpetuating. This is their work. It is not Jewish Americans’ job to do it for them. But it is important that Jewish Americans, for their own sake, be willing to state that antizionism is itself a form of oppression. One does not need to label it antisemitism to make that point. Were its history better known, the term “antizionism” would bear the stigma of the evils committed in its name. But who knows this history well besides émigrés who remember their treatment as Jews under the Soviet and Iranian regimes? For this reason, their voices are among the most important in the Jewish American community. Dialogue with the newest immigrants can help Jewish Americans take Poliakov’s dictum—that antizionism differs “depending on the region and the regime”—and use it to navigate their difficult situation.

Finally, Jewish Americans must tackle the problem of the “sample of one.” This means reinventing Jewish education to present Nazi antisemitism not as the paradigmatic example of twentieth-century anti-Jewish oppression but as one of its two major variants—the one rooted in the culture of the political right. This will require developing supplementary school, day school, summer camp, and youth group curricula for all age levels about Soviet and Iranian antizionism. By devoting equal time to this subject, Jewish children and their parents, too, will more easily recognize that the Othering of Jews is just as much a tradition of the political left, and will be capable of specifying how and why.

Then, real education can begin. How do these historical experiences of anti-Jewish oppression overlap or diverge? How could anti-Nazi Communists and anti-Communist Nazis both find in Jews a common enemy? How did each society mobilize its reigning academic paradigms (scientific racism, Marxist anti-imperialism) to justify discriminatory practices against Jews? What are the legacies of each in American politics and American education today? And regardless of whether one self-identifies as progressive, liberal, moderate, or conservative, how can one recognize and fight against the anti-Jewish inheritance of one’s own political camp?

Would it also be possible to write the study of Soviet antizionism into American public school curricula? Had such an education been a regular part of American high school education, college students might have been less likely to join the antizionist wave that engulfed campuses with the start of the Al-Aqsa Flood. Or perhaps not. But at least they would not have embraced antizionism out of ignorance. Those who joined the encampments would have done so with the understanding that their politics come with an uncomfortable history. Then they could make the moral choice to confront this history or to knowingly ignore it.

We are unlikely to witness the study of Soviet antizionism in American public schools, however. High school history curricula are already overpacked, and the Cold War itself is barely treated. Curricular reform of this sort is a tall order.

But American Jews do have the power to change Jewish education. They cannot undo their failure to prepare their children who faced hostility on campus in 2023 and 2024 and 2025. But they can start now to teach the class of 2030 about the long and unsavory history of antizionism so that they will understand more about it than any of their professors or classmates who practice it in dangerous ignorance.