In Praise of Compromise: Two Models for Navigating Conflicting Values

Joshua Kullock

Joshua Kullock serves as the rabbi of West End Synagogue in Nashville, TN.

Two years after October 7 and its devastating reverberations, Jews in Israel and around the world face urgent questions of survival, loyalty, justice, and peace. We contend not only with a surge in antisemitism from across the ideological spectrum but also with the mounting pressures of internal division. Within our own communities, competing voices press their beliefs with growing intensity. Left unchecked, these forces threaten to pull us apart—not only from one another, but also from the shared values we claim to uphold. Today, polarization stands out as our paramount challenge.

Polarization fuels binary thinking. Research on political polarization shows that as people become more entrenched—more convinced of their own rightness—they elevate their personal positions into dogma. For those at the extremes, compromise feels like heresy: If I am absolutely right, then affirming another perspective is tantamount to treason. In such a situation, embracing complexity—or living within the tension of competing truths—is nearly impossible. And yet, complexity may be precisely where wisdom lives.

This essay seeks to recover a moral framework, rooted in Jewish tradition—that invites us to rethink our assumptions and reimagine compromise not as weakness, but as a form of strength. At its heart is a simple insight: Wisdom does not lie in choosing a single, absolute value, but in the practice of holding multiple, often competing commitments—embracing the tension rather than seeking premature resolution.

To be sure, this is a tall order. Core principles periodically come into conflict, pulling us toward different goals. Sometimes these tensions demand a choice; other times, they call for the ability to balance opposing commitments in pursuit of the best possible outcome. Developing such frameworks can help us navigate some of today’s most pressing challenges. In what follows, I turn to a remarkable story from the Babylonian Talmud—one that offers vital lessons on this subject.

Hierarchy and Its Discontents

In bChullin 60b, we read:

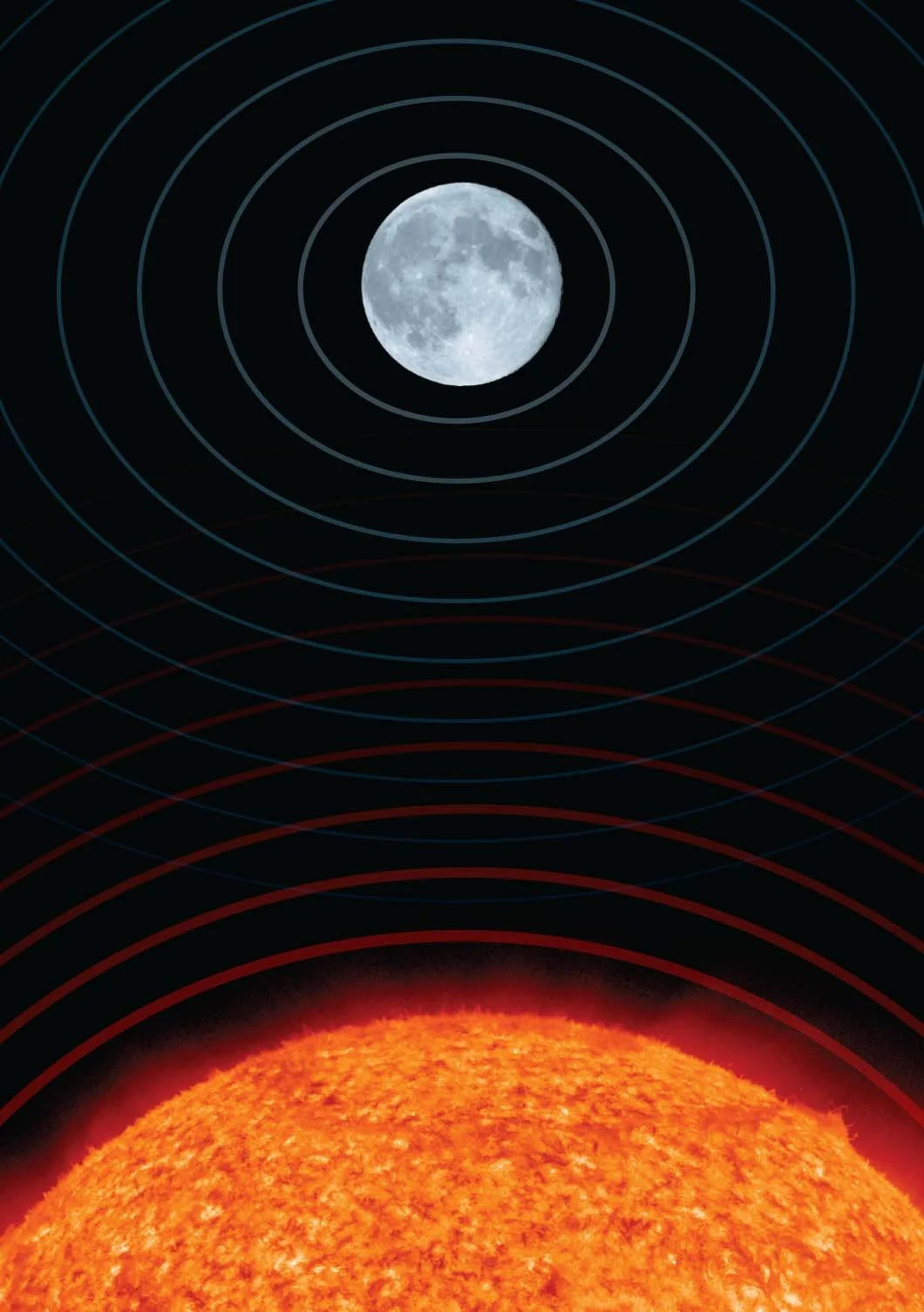

Rabbi Shimon ben Pazi raises a contradiction. It is written: “And God made the two great lights” (Gen. 1:16), and it is written: “The greater light... and the lesser light” (ibid).

The moon said before the Holy One, Blessed be He: Master of the Universe, is it possible for two kings to serve with one crown?

God said to her: Go and diminish yourself.

She said before Him: Master of the Universe, since I said a proper thing before You, must I diminish myself?

God said to her: Go and rule during the day and during the night.

She said to Him: What is so great about that? What use is a candle in the middle of the day?

God said to her: Go, let the Jewish people count the days and years with you.

She said to God: But they use the sun as well, as it is impossible that they will not count seasons with it, as it is written: “And let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years” (Gen. 1:14).

God said to her: Go, let righteous men be named after you: Ya’akov the little one, Shmuel the little one, David the little one.

God saw that the moon was not comforted. The Holy One, Blessed be He, said: Bring atonement for me, since I diminished the moon.

And this is what Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish says: What is different about the goat offering of the New Moon, that it is stated with regard to it: “For Adonai” (Num. 28:15)? The Holy One, Blessed be He, said: This goat shall be an atonement for Me for having diminished the moon.

This story operates on multiple levels. On one level, it’s an etiological tale, explaining why the moon is smaller than the sun. On another, it showcases the rabbis’ deep attentiveness to textual nuance. Rabbi Shimon ben Pazi highlights a tension within a single verse: How can both luminaries be called “great” if one is later labeled “lesser”? Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish, in turn, makes a bold theological move, interpreting the unique Hebrew phrasing of the Rosh Chodesh offering—la’Adonai—as a sacrifice not to God, but for God: an act of atonement for having diminished the moon.

Both traditional and modern commentators often read this story as a lesson in humility. Rashi, for instance, in his comment to Genesis 1:16, suggests the moon was diminished because she “complained,” seeking the crown for herself. Building on this, scholar Yonah Frankel understands God’s response as a pedagogical act: The demand for a sin offering is not a confession of divine guilt but a moral gesture, God humbling Godself in order to teach the moon a lesson in modesty. Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas pushes his interpretation in a different direction. For him, the tale is not merely didactic but revelatory: an instance of divine kenosis—a self-emptying or tzimtzum—through which God affirms that true greatness lies in limitation, smallness, and humility, the very conditions necessary for making space for the Other.

The problem with many of these explanations is that the Talmud never describes the moon’s question as a complaint. That language is used in other midrashim, such as Midrash Konen, but not in our sugya. Since our Talmudic vignette does not describe the moon as complaining and instead includes the motif of God seeking ways to appease her, it prompts important questions: What were the rabbis trying to convey by telling the story this way? What lessons were they hoping to impart through this particular framing?

God’s mistake, I suggest, stems from responding too hastily to the moon—hearing its question as rhetorical when it was meant as a sincere challenge. By assuming that two equal lights cannot coexist—that power, values, or truths must always be singular and hierarchical—God affirmed the very limits the moon sought to unsettle. Read this way, the moon’s inquiry, “Is it possible for two kings to serve with one crown?” becomes not a complaint but a provocation, directed at both God and every reader, urging us to imagine a reality in which power can be shared; truth can hold multiple and, at times, even opposing layers; and values need not conform to a fixed order. Perhaps, then, the problem was never the moon’s question but God’s momentary lapse of faith in creation’s ability to uphold this ideal of tension in balance. In asking the moon to diminish, God abandoned the vision of shared sovereignty only to realize that a world built on static hierarchies can become deeply problematic. That, I believe, is the very notion God came to regret.

When we operate under a fixed hierarchical order—when the sun is always bigger than the moon, truth always outranks justice, and self-preservation always trumps compromise—our ability to navigate complex realities shrinks. Consistently arranging values in the same way, irrespective of context or nuance, robs us of the flexibility we need to respond wisely. Worse yet, despite our best intentions, rigidly prioritizing one value over the rest may set us on a path toward the very extremism and zealotry we condemn. As the Israeli writer Amos Oz observed in his 2006 book How to Cure a Fanatic:

Fanaticism is extremely catching, more contagious than any virus. You might easily contract fanaticism even as you are trying to defeat it or combat it. You have only to read a newspaper, or watch the television news, and you can see how easily people may become anti-fanatic fanatics, anti-fundamentalist zealots, anti-Jihad crusaders.

The Talmudic sages were keenly aware of the dangers of elevating any value into an absolute, and they scattered cautionary tales throughout rabbinic literature as an antidote to this pervasive malaise. Time and again, they show us that an unwavering and exclusive devotion to any single noble value—whether it is to truth, modesty, tzedakah, humility, love of God, judgment, or peace—can lead to disastrous consequences.

We see a similar trend within the halakhic discourse. To ensure that halakha did not become absolute, the rabbis established mechanisms through which the law could, at times, be overruled. Principles such as pikuach nefesh (saving a life) or sha’at had’chak (extenuating circumstances) serve as tools that allow the system to override itself to preserve its greater purpose. As Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish says in bMenachot 99b: “Sometimes the nullification of Torah is its foundation.” Such legal flexibility expresses the moral insight animating our conversation: No single value should govern every situation, and the only way forward lies in learning how and when to enact the many values we hold dear. That’s why the rabbis, for example, prohibited giving more than one-fifth of one’s wealth to tzedakah.

So, is it possible for two kings to serve with one crown? Is it possible for mercy and justice, love and critique, tradition and change, faith and doubt, to share one crown in our fractured and aching world? In what follows, I would like to offer two answers that take the moon’s question seriously and provide alternative models to the concerns it raises.

Lifting Up Different Values at Different Times

My first answer to the moon’s challenge remains negative—two kings cannot share the same crown at the same time—but with a crucial distinction. Rather than clinging to a fixed hierarchy where a single value always prevails, my approach embraces a dynamic system in which different ideals take turns holding the crown. Instead of committing exclusively to one guiding principle, we are called to shift between values depending on the broader context, changing conditions, and the specific moral demands of any given moment.

For instance, consider the war in Gaza. In the early stages, individuals committed exclusively to peace likely found it difficult to endorse Israel’s military engagement. Conversely, two years later, following the ceasefire that began this past October, those focused solely on territorial integrity still struggle to recognize the value of a negotiated agreement—one that not only secured the return of all the living hostages, provides for the return of the remaining bodies for proper burial, but will eventually require the IDF to withdraw from significant portions of the Strip.

Likewise, in the first months after October 7, a heightened sense of self-preservation drew many within the Jewish community to support the war against Hamas. At the outset, the war was widely understood as both just and necessary. Solidarity reigned, rooted in the belief that the survival of the Jewish State was at stake. In those days, it was virtually impossible for most to imagine a different conversation. Yet, as events unfolded, other central truths gradually began to claim their place.

A commitment to truth means grappling with difficult questions. In Israel, this requires establishing a commission of inquiry to examine shortcomings in the country’s security planning and its assumptions regarding neighboring actors and threats. It should also confront the complex consequences of military operations for civilians in Gaza and consider measures to uphold responsibility and minimize harm. In the Diaspora, it calls for honest reflection on our own responses: for some, this means confronting biases that have led us to avoid moral critique of the Israeli government; for others, it means reckoning with the possibility that, in opposing the war or publicly voicing harsh criticism against Israel, we may have inadvertently empowered those whose agenda is not the protection of Palestinian lives but the disappearance of the Jewish State. The shift from unity to accountability is no simple task, but it is precisely in moving between key values that moral clarity—and radical hope—can emerge.

Confronting the hard choices that a dynamic value system places before us requires humility and compromise: humility, because once we move away from the assumption that a single value will always guide our decisions, we enter a more uncertain and demanding arena, one in which each situation calls for careful examination; and compromise, because embracing a dynamic hierarchy of values means pursuing an ongoing process of internal negotiation, constantly weighing competing principles, each offering us a distinct vision of what is right.

Holding competing values simultaneously can lead us to moments of existential pain or even paralysis. There is no formula that guarantees the right answer—only the disciplined work of moral discernment. But perhaps this very uncertainty is a feature, not a flaw. It invites us into deeper listening, broader empathy, and a willingness to live with our own imperfection while striving for integrity.

Most human beings share a core set of values: truth, peace, justice, humility, self-preservation, pluralism, inclusion, and others. Differences often lie not in which values we hold dear but in how we apply and prioritize them. If we can acknowledge this complex reality—how certain circumstances, for example, might lead us to place peace above self-preservation, even when both feel central to who we are—we may grow more compassionate toward others who choose differently. Their path may diverge from ours not because they lack values, but because, in that particular moment, they lifted a different value to the forefront.

Our commitment to a pluralism of values still has boundaries. Some agendas fall so far outside our shared moral field that they cannot be included at all. Racism, dehumanization, and calls for the destruction or mass displacement of others are corrosive ideologies that must be rejected outright. The discipline of compromise should never be confused with surrendering to hatred or with the endorsement of supremacists of any kind. Recognizing the tension between values can never become an excuse to blur the line between good and evil. In other words, learning to balance between values is not a call for moral relativism.

The Crown of Compromise

My second answer to the moon’s question offers a very different approach, replying in the affirmative: At certain moments, it is not only possible but necessary for two kings to reign with one crown. Although relying on a single guiding principle may feel simpler, many of life’s challenges call for something else—not for the selection of one value over another, but for the ability to hold competing ideals in tension and to navigate their interplay with sensitivity and attentiveness.

In a similar vein, Isaiah Berlin wrote:

The collisions, even if they cannot be avoided, can be softened. Claims can be balanced, compromises can be reached: in concrete situations not every claim is of equal force—so much liberty and so much equality; so much for sharp moral condemnation, and so much for understanding a given human situation; so much for the full force of the law, and so much for the prerogative of mercy; for feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, healing the sick, sheltering the homeless. Priorities, never final and absolute, must be established.

The first public obligation is to avoid extremes of suffering. . . . The best that can be done, as a general rule, is to maintain a precarious equilibrium that will prevent the occurrence of desperate situations, of intolerable choices—that is the first requirement for a decent society; one that we can always strive for, in light of the limited range of our knowledge, and even of our imperfect understanding of individuals and societies. A certain humility in these matters is very necessary. ( “The Pursuit of the Ideal”)

In the wake of October 7, few relationships as poignantly embody the challenge of holding simultaneous competing values as our love for Israel—deep and enduring, yet never uncritical. For many of us, this love is woven into Jewish identity, history, and collective memory, forming a foundational part of who we are. Yet genuine affection should not demand silence or blind loyalty. Rather, it calls us to hold Israel to its highest ideals, speaking honestly and compassionately when moral concerns arise. This friction between profound attachment and courageous critique is not a contradiction but a vital coexistence. It asks us to resist the impulse to choose between love and condemnation and to instead embrace the difficult work of holding both together. To love and to criticize simultaneously is a sacred act of loyalty: a recognition that true commitment sometimes means challenging what we cherish most. Today, guiding communities as they navigate these tensions might be the most urgent responsibility of rabbis and communal leaders alike.

This second model works particularly well when applied to commensurable values, those that lie along a shared axis and can be weighed against each other. In such cases, the challenge lies in determining how to balance competing priorities within a common moral or conceptual framework. Instead of choosing between humility and assertion, freedom and equality, or individual rights and the common good, we must learn—under the auspices of a shared crown—how to compromise and commit to both.

Consider this in light of democratic governance: the essence of democracy lies in distributing power across multiple branches, creating a system of checks and balances that preserves the integrity of the whole. The Talmudic metaphor of a crown likely served Jews well in a pre-democratic context, offering a vivid image for leadership and moral guidance. As a symbol for shared power and the integration of multiple values in our contemporary democracies, it has its limitations. Still, it remains the language we have, and it is on us to ensure it is not taken as license to hoard power. History provides ample evidence of the dangers arising when a single authority rules without constraint.

Setting the crown metaphor aside, the idea of balancing between different forces is well grounded in our sources. Midrash Temurah, for example, teaches us that God created the world in pairs, “to make known to them that everything has a partner…, and were it not for the one, the other would not be” (Ch. 1). Similarly, Bereishit Rabbah offers a powerful metaphor for divine compromise:

This is analogous to a king who had empty cups. The king said: If I pour hot water into them, they will shatter; if I pour cold water, they will crack. What did the king do? He mixed hot and cold water and placed it in them, and they endured. So, the Holy One said: If I create the world with the attribute of mercy, there will be many sinners; if with the attribute of strict justice, how will the world endure? Rather, I will create it with the attribute of justice and the attribute of mercy, and hopefully it will endure (12:15).

Applied to our conversation, this midrash teaches us that we are not meant to resolve the friction between competing ideals by discarding one for the other. In this context, compromise becomes essential—not in the sense of giving up, but as the moral discipline of limiting each value’s absolutist pull to preserve the whole. Especially now, Jewish leaders are called to nurture communities that are both particular and universal; to reconcile a Judaism faithful to its traditions yet open to change; and to continue to dream of—and work for—an Israel that honors both its democratic and Jewish identities.

In practice, these two models for navigating conflicting values are complementary, and their use should be guided by context. At times, the crown must pass from one value to another as conditions shift. We saw this when weighing the competing claims of self-preservation and peace, or solidarity and accountability. Yet there are also situations that call for holding multiple values together, allowing them to coexist in productive tension, each shaping our decisions without overpowering the rest.

Fostering the development of these two alternative answers to the moon, particularly in the aftermath of October 7, requires spiritual courage and moral imagination. Rabbis and communal leaders must encourage conversations in which rival claims can stand side by side without being collapsed into a rigid hierarchy or silenced by the lure of absolutes. This means shaping our congregations to become communities of care and forums for open dialogue, practicing the art of radical listening, and supporting initiatives that address both urgent needs and long-term ethical responsibilities. On this basis, we can bring our people together as we sustain a shared, complex discourse that upholds national security while demanding that humanitarian aid reaches civilians in Gaza, teaches about the atrocities committed by Hamas while cultivating empathy for the Palestinian people, and wrestles with fear and grief without being overtaken by anger or blame.

It is important to remember that the vision of two kings serving with one crown—or, in our reading, multiple values coexisting—was the original divine plan. The imbalance between the luminaries was God’s response to the moon’s inquiry, a move God later came to regret. In the end, as it was in the beginning, both hot and cold are needed if the world is to thrive. We need mercy, and we need justice. We need tradition and change, self-preservation and altruism, obligation, and choice. We need truth—and we need peace.

Compromise, as presented here, is not weakness but a sacred discipline. In a world increasingly torn by polarization and threatened by the widening abyss carved by extremists, compromise may be the only bridge strong enough to gather us together and carry us ahead. Our tradition entrusts us not only to atone for God, as the Talmudic sages radically imagined, but to partner with God in the slow, often painful, but ultimately redemptive work of leading the world—and the Jewish people—toward what it was always meant to become.

So, to you, diminished moon, we say: Your question still guides us, and your challenge still endures. Wisdom does not lie in elevating one luminary above all others, but in learning how to let many lights shine in concert—truths, values, and ideals intertwined, each shaping the whole without extinguishing the rest—until the day comes when, as the prophet Isaiah envisioned (30:26), “the light of the moon shall become like the light of the sun.”