Trauma and Its Challenges, Resilience and Its Shadow: What Holds Israeli Society Together and What Holds It Back

Shoshana Cohen

Shoshana Cohen is a Research Fellow at the Kogod Research Center at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, is on the faculty of the Rabbinical School of the Schechter Institute, and leads the beit midrash at the Dorot Fellowship in Israel.

There is a famous story in the Talmud that begins with the phrase, “a person should always be flexible as a reed rather than strong as a cedar” (bTa’anit 20a). I thought of it one Thursday night right after Israel’s ceasefire with Iran began this past June. It was my son’s high school graduation, a quiet night, without planes flying overhead, and without sirens. The song the graduates chose to sing, “Manginah” (The Tune), expresses a longing to know what is coming, whether it will be good or bad. The chorus is ambivalent: “Sometimes I’m above the waves/ Sometimes I’m under them, / But either way, / I love the sea.”

My son and his friends are coming of age in a time of particular struggle and uncertainty: because of Covid lockdowns, labor strikes, and wars, they have been in and out of school for the last six years. The night before their senior year began, they learned that Hersh Goldberg-Polin—who most of them knew from the neighborhood or from the Hapoal Jerusalem Fan Club—and five other hostages had been found dead in a tunnel in Gaza.

The material and social destruction that Israeli society has suffered since October 7 (and even before) cannot be overstated. Entire communities have been displaced; in addition to the civilian victims of October 7, we have lost many soldiers, and families are mourning these unbearable losses. The political system is in crisis, public trust is eroded, the death toll in Gaza is enormous, and the future continues to feel uncertain.

Sociologist Kai Erikson defines collective trauma as “a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of community.… ‘I’ continue to exist, though damaged… but ‘we’ no longer exist as a connected pair or as linked cells in a larger communal body.” By this account, trauma dissolves the connective tissue of society, leaving people isolated within their pain. Yet the Israeli case tells a more complicated story. The same forces that might have fractured collective identity seemingly have instead reinforced it. Networks of care, civic volunteerism, shared rituals, and a deeply rooted sense of peoplehood have so far prevented the “we” from collapsing. Israelis did not escape trauma; we transformed its isolating energy into connection, meaning, and responsibility. Through it all, much of the fabric of society has held. People continued to show up—to volunteer, to protest, to argue, to grieve. During the worst times, I wondered: What explains this capacity to keep going, not only materially, but emotionally, socially, spiritually, and psychologically? Now I am asking how the experience of trauma, and the distinctive tools of Israeli resilience, will shape our future. I am asking these questions from the perspective of a Jewish Israeli, and these observations are primarily about my own ethnic and religious group within Israeli society. As we will see, the same story of resilience for some can mean the opposite for others who are not part of the same collective.

The answers are not simple. Israeli resilience is not always a conscious or intentional choice. As an olah, an immigrant, raising sabras, native-born Israelis, I marvel at (and participate in) Israeli resilience even as I am ever aware of its dangers. Israeli society relies upon a set of deeply embedded cultural practices and habits that are often unspoken, taken for granted, or instinctive, as they shape the way individuals and communities respond to crisis. They do not eliminate trauma, but they structure it, helping people to remain engaged, connected, and oriented toward meaning through repeated, ongoing, and persistent traumas, even under the most intense pressure.

At the same time, while these mechanisms allow Israelis to continue to exist and to survive as individuals, in community, and even as a society, they present dangers of their own. Below, I will explain what I have come to see as distinctively Israeli modes of resilience, many of which are rooted in Jewish values and traditions. I’ll also offer some of reflections on the risks these modes of resilience pose to our society, including how they affect Palestinian Israelis.

Modes of Resilience

1. A Penchant for Meaning Making

One of Israelis’ most notable modes of resilience is their penchant for narrative framing and meaning making. Rather than treat each crisis as a discrete event, Israeli Jews, like Jews throughout history and around the world, often locate it within the larger arc of Jewish history.

In the introduction to their fascinating anthology, Bible Through the Lens of Trauma (2016), Elizabeth Boase and Christopher G. Frechette write:

Constructing a trauma narrative is an act of meaning making.… Such interpretation has the task of supporting a sense of order, identity, agency, well-being, and solidarity, while also expressing the impossibility of fully comprehending the trauma.

This habit is reinforced by textual and ritual traditions. The vehi she’amda passage from the Passover Haggadah, recited every year at the seder and made even more famous among Israelis by the singer Yonatan Razel, resonated particularly strongly in April 2024 and again in April 2025: In every generation they rise up to destroy us, but the Holy One, Blessed be He, delivers us from their hands.

The message of vehi she’amda is twofold: On the one hand, it affirms that Jewish existence always was and always will be about oppression and suffering at the hands of our enemies. On the other hand, it affirms that it is neither strength nor fortune that sustains the Jewish people, but covenant and continuity in the face of repeated oppressions. These lines are more than liturgy—they are interpretive tools. They give contemporary suffering a place in an enduring story, one in which survival and purpose are not only possible but have meaning. Though they might disrupt Israeli Jews’ immediate sense of themselves, trauma and suffering not only fit the meta-narrative of Jewish history expressed in this passage (and many others) but also strengthen it, make it real, and allow it to provide hope and direction.

2. Ritual and Rhythm

When trauma disrupts the rhythms and coherence of daily life, we lose our bearings and struggle to know how or when to act. Judaism provides ritual structures that help restore a sense of orientation. As Boase points out in the anthology mentioned above,

Literature on recovery from trauma widely acknowledges the importance of narrative in the process of healing.… The formation of a new metanarrative… represents a revised framework of understanding that can “assimilate the reality of trauma.”… At the level of collective identity, trauma is socially mediated, woven into communal memory through acts of representation and meaning making.

With its cycle of weekly Torah readings, holidays, and fast days, the Jewish calendar creates a rhythm in which ancient stories intersect with the moral and emotional crises of the present, and even when words fail, these rituals can provide religious Jews with a source of meaning. Secular Israelis, too, rely on Jewish ritual, aspects of which permeate Israeli culture: A tragedy near Purim may call up the figures of Esther or Amalek, while Yom Hazikaron evokes both biblical and civic registers of mourning at ceremonies that use David’s lament over Jonathan from the first book of Samuel as an expression of grief for newly fallen soldiers. A striking new example is “Kinat Be’eri,” the lament composed by Yagel Harush in the aftermath of October 7, which was woven into Tisha b’Av services in many communities, where it joins laments from earlier times of hardship and grief, from the Crusades to the Holocaust, in an ever expanding canon of laments.

Tekasim, public ceremonies, are a central ritual of Israeli civic religion, and they function as an important coping mechanism. At a tekes, Israelis create space for memory, grief, and solidarity through a familiar structure of music, silence, poetry, and symbolic action. At tekasim over the last two years, names of new victims and fallen soldiers were integrated into existing memorials; new songs, composed in response to current traumas, were played between older ones, as we mourned and commemorated through song and ceremony. A tekes cannot repair what has been shattered, but names it, holds it, and gives it form, restoring coherence and meaning in the face of rupture.

3. Language and Loss

In moments of profound trauma, people often find themselves unable to describe what is happening or how they feel. Pain overwhelms words, and language collapses. Jewish tradition responds to this fragility by offering a vocabulary. The depth and diversity of Jewish texts provide not only frameworks of thought but also ready-made words for grief, protest, hope, and complexity. Psalms, the book of Eichah (Lamentations), midrashim, and liturgy are reservoirs of expression when ordinary speech falters. In the months after October 7, I returned again and again to Eichah with my students. To my surprise, its sometimes grotesque and often brutal descriptions of the destruction of the First Temple gave us a measure of comfort, offering language for the unbearable realities we had recently faced. Instead of being struck dumb before the horrors of that day, the biblical words gave voice to pain we could not otherwise name.

There is deep power in fixed language when confronting trauma: Even before it forms a coherent story, it begins to absorb, contain, and slowly process the experience of loss.

4. Action Over Passivity

Suffering and violation can push us into a state of extreme passivity. Recovery from trauma often involves reclaiming control—choosing to act rather than remain passive. Here, too, the Zionist ethos, which has at its core a preference for action over passivity, provides a powerful tool for resilience. Israeli society instinctively responds to crisis with activity: organizing relief, delivering supplies, rebuilding communities, showing up in solidarity. This reflex is not incidental—it is rooted in the origin story of Zionism itself. As Einat Wilf writes in “The Intersectional Power of Zionism” (2016):

Zionism was a rebellion against Jewish passivity. To the Jewish people, Zionism carried the message that they need not wait for the Messiah. Rather, they should be their own Messiahs.… Zionism demonstrated that, even when dealt some of the worst cards in history, humans were active agents, capable of changing the course of their private and collective futures.

That ethic continues to animate public life. On October 7, volunteers drove south to evacuate survivors. After the disasters of the last two years, WhatsApp groups filled with offers of food and supplies. Protesters flooded the streets. There is rarely a vacuum of Jewish response in Israel.

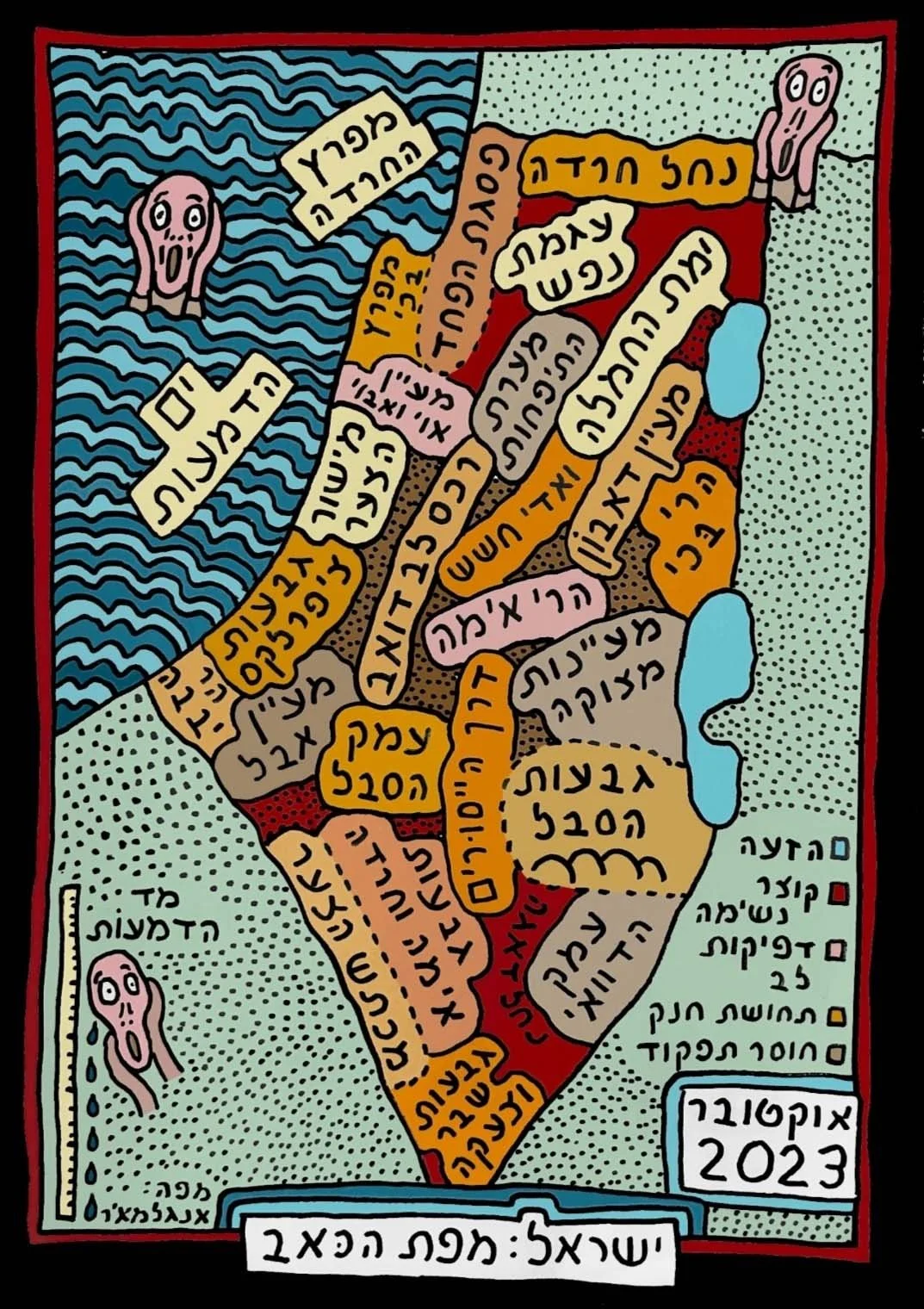

In the days immediately following October 7, visual and performance artist Ze’ev Engelmayer released Map of Pain, and soon after, Map of Hope—two drawings that transform Israel’s geography into an emotional landscape. The first renders the country as a single field of collective paralysis: every region renamed for grief, fear, and anxiety, its dark colors dissolving the boundaries between individual and national pain. The image is framed by Munch’s The Scream, a haunting emblem of shared terror and helplessness. The second, created shortly afterward, reuses the same geography but fills it with light and warmth, supplanting The Scream with a radiant sun and replacing anguish with gestures of generosity, volunteering, and care. Together, the two maps trace a movement from solidarity in pain to solidarity in action—from a nation frozen by trauma to one mobilized by compassion.

5. Networks of Care

Israelis were among the earliest adopters of WhatsApp because of its group chat feature. The platform mirrored their real lives, where most people are members of multiple, long-standing circles of banter, memory, and intimacy. In times of crisis, these circles are not merely activated—they are assumed. Even if support is not actively flowing from every network at every moment, most Israelis live with a palpable sense that many others care about them. That alone does a lot to counter the loneliness and despair that trauma brings. Circles of grief and solidarity ripple outward, reaching well beyond immediate kinship into wider webs of responsibility.

The poet Yehuda Amichai captured this ripple effect in his 1975 poem, “The Diameter of the Bomb”:

The diameter of the bomb was thirty centimeters

and the diameter of its effective range about seven meters,

with four dead and eleven wounded.

And around these, in a larger circle

of pain and time, two hospitals are scattered

and one graveyard. But the young woman

who was buried in the city she came from,

at a distance of more than a hundred kilometers,

enlarges the circle considerably,

and the solitary man mourning her death

at the distant shores of a country far across the sea

includes the entire world in the circle.

Amichai’s poem expresses a universal truth: Any individual killed in a tragedy leaves behind a web of people bound to them and sharing the pain of their loss. And yet, the poem also feels particularly rooted and resonant in the close-knit Israeli networks of connection and in the wider bonds of Jewish peoplehood.

6. A Socialist Collectivist Ethic

At its founding, Israel was a nationalist, socialist society with a deep sense of Jewish peoplehood and a conviction that collective commitments take priority over individual desires. While Israeli society has grown more individualistic and capitalistic over the decades—particularly since the Six-Day War—the socialist ethos has not disappeared. We can see this in the educational system, much of which centers on learning how to function within a group: how to cooperate, negotiate, and balance personal needs with the needs of others. Israeli children are placed into class groups in first grade and remain in those same groups through elementary school. Unless special circumstances demand otherwise, classes are never reshuffled. Further, an Israeli classroom itself belongs to the students rather than the teachers; the children stay put while their instructors rotate in and out during the day. The class group becomes a child’s primary social unit, often shaping not only their school experience but their lifelong social groups.

Recent years of trauma and loss have continually demanded sacrifice: comfort, personal plans, and, most painfully, the lives of sons and daughters—all offered up for the preservation of the collective. This orientation can be a powerful source of resilience, but it is not without peril. Israelis are socialized to believe that “it’s not about you,” and this can provide a sense of purpose and transcendence of everyday demands. But when Israelis are continuously asked to sacrifice their children and themselves to a cause whose goal is unclear, or when the needs of one group within the collective clash with those of another, the consequences of this belief become far more troubling.

7. Pronatalism (Focus on the Kids)

One of trauma’s most devastating effects is its collapse of time: Survivors feel trapped in the past or stuck in the present, unable to imagine a future. In another article in Boase and Frechette’s anthology, Robert Schreiter writes, “[Trauma] shows… how past and present become disconnected, how temporality itself is suppressed.… The tyranny of past events that freezes us in an unending past and that blocks out the present and the future must be overcome.”

Israeli society is profoundly pronatalist, and the act of giving birth and raising children generates hope, continuity, and purpose—sometimes consciously, often unconsciously. This is a universal dynamic. In a recent study of over 43,000 people across 30 European countries published in the Journal of Marriage and Family, psychologists and sociologists note this dynamic more broadly: While parenthood does not consistently increase day-to-day happiness, it is strongly associated with a heightened sense of meaning and value in life.

Israeli pronatalism is reinforced by strong state systems that support families. Parenthood is assumed as a default, and much of adult life revolves around raising children. This orientation provides more than comfort: It offers a living rebuttal to despair, grounding people in a sense of future even when that future is uncertain.

Trauma has helped to cement pronatalism as a central cultural value in Israel. In many societies over time, wars have been followed by baby booms; the idea that Israelis (or Jews more broadly) must “have children to replace those lost in the Holocaust” is explicit within Haredi communities, but its influence quietly permeates secular culture as well. Most recently, the country’s birth rate has seen a small rise since October 7. Interestingly, the relatively high birthrate and pronatalist culture in Israel is true across the board and includes Palestinian citizens as well.

The cultural imperative to raise families in the face of loss and hardship can be a source of resilience: it turns a parent’s attention outward, channels despair into care, and insists that life must continue. Even in wartime, parents devote themselves to their children’s daily needs—play, school, even celebration. The common refrain “for the sake of the kids” captures a collective conviction that hope, vitality, and an orientation toward the future are obligations. While not every parent experiences young children as a source of joy, many do, and in a child-centered society, those sparks of joy and inspiration often emerge even when hope should feel most elusive.

8. Emotional Openness

The stereotype of Israelis as blunt and outspoken holds a kernel of truth: We tend to prize openness over repression, and people often speak their minds quickly, loudly, and directly, despite our ethos of “soldiering on.” Israel permits outrage, uncertainty, and vulnerability to be voiced without shame, and emotion is woven into public life in eulogies and protest chants, in poetry and news interviews, and around Shabbat tables. This cultural openness operates as a pressure valve; allowing emotions to be aired, processed, and validated in the moment keeps them from building up into a destructive force.

The Shadows of Resilience

These cultural forms have helped Israeli society survive. But survival is not the same as healing and rebuilding—and, as I’ve already hinted above, resilience, too, has its shadows.

1. The Loss of Dreams

“When the Lord restored the fortunes of Zion, we were like dreamers” (Ps 126:1).

This line from Psalm 126, recited at the end of every Shabbat and holiday before Birkat Hamazon, the grace after meals, captures the astonishment of an ancient people who never expected to return to the Land of Israel. Yet from its inception, Zionism has insisted that its “dreamers” do not only marvel at miracles—they seize the chance to imagine and build anew.

The “Zionist dream” is greater than the physical return of Jews to the land. Zionism is a movement imagining and striving toward an ideal society. Early visions differed—some saw socialism, others religious renewal, still others cultural revival—but the act of dreaming itself was foundational. Writing and art centered on visions of what might be have always nourished Israel’s sense of mission and hope.

Today, I see that imaginative energy is under siege as a sense of prolonged crisis and repeated trauma corrodes our capacity to dream of a better reality. The more a society normalizes trauma, the easier it is to forget what “normal” should feel like, let alone conceive of the good. When imagination shrinks to mere survival, moral and political vision falters.

2. Numbness

Emotional numbness is a natural, necessary, response to acute trauma—our systems can become so overwhelmed with pain and fear that the only recourse is to stop feeling altogether. But if this survival mechanism remains in gear, it can have devastating emotional and moral consequences. What began as self-preservation can calcify into a refusal, or perhaps an inability, to feel across the human divide. Numbness may help explain why many Jewish Israelis struggle to acknowledge the depth of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza or to extend empathy to Palestinians. This absence of feeling is not neutral—it is a profound obstacle to envisioning a shared future for both peoples and for demanding the end to all suffering caused by this war and the conflict in general. Israeli poet Yael Stateman captured this sort of emotional numbness in her poem, “To A Friend Who Looks at Starving Children in Gaza and Feels Nothing,” from March 2024, which includes the lines:

And she does not

Concern herself with the other side,

And she is neither proud of it nor denies it,

And she does not love that this is how it is—

But this is how it is.

A study published this past summer by the aChord Center at Hebrew University found that 62 percent of Israelis agree with the statement, “There are no innocents in Gaza”; among Jewish Israelis, the number rises to 76 percent. We are no longer merely worrying about the possibility of emotional numbness and its effect on policy—we are already living within its reality.

3. Isolation

Earlier, I noted that Israel’s dense social networks and strong sense of collective belonging are central to its resilience and survival. Yet these very strengths can also generate moral blind spots. In moments of crisis, Jewish Israelis often turn inward, reinforcing their sense of themselves as “a people that dwells alone, that is not reckoned among the nations” (Num. 23:9).

This posture of “separateness” can serve as protection, but it can also become a kind of prison. It can lead policymakers to assert that Israel can rely only on itself, rendering all international moral and political expectations irrelevant. This is an abandonment of the Zionist goal that, with a state, the Jewish people would enter the family of nations; it is also dangerous, since it allows Israel to avoid accountability.

There is also an unmistakable irony in the notion that Israel is alone and can rely only on itself: Since its inception, Israel has received more American foreign aid than any country in history—over $300 billion in total, with record-breaking sums since October 7, 2023. During the conflicts with Iran over the past year and a half, US and other allied forces intervened directly, deploying military assets in joint defense. Even during that action, there were forces within and outside of Israel that put this position at risk.

4. Jewish Chauvinism

The war—and the social networks it has activated—have amplified a Talmudic principle widely accepted by Israeli Jews: “the poor of your city take precedence” (bBava Metzia 71a). Under conditions of existential threat, the barrier between “us” and “them” hardens. For most Israelis, the devastation in Gaza or the West Bank is not their loss; those who suffer there are not “our people,” and are seen as enemies, unworthy of compassion. It is this type of sentiment that has allowed rampant settler violence in the West Bank against Palestinians to go, until very recently, largely unnoticed by the broader Israeli public.

When Israeli meaning making focuses on an epic Jewish story, non-Jews among Israel’s citizens are excluded from the very collective that holds the rest of society together. This exclusion is by no means symbolic—within Israel, the standing of Palestinian citizens has deteriorated dramatically since the war’s onset, shaped by the suspicion that they cannot be fully trusted.

There have been moments when solidarity did cross ethnic and religious boundaries. The stories of the many Druze killed in missile attacks and as soldiers, and of Bedouin victims of October 7, including hostages, have been told in the media and at rallies and memorials. And yet these are limited to citizens of Israel and do not include Palestinians in the West Bank or Gaza. In addition, despite such displays of solidarity, the Palestinian Israeli community has continued to suffer from increased violence and a severe lack resources.

More generally, while the Yom Hazikaron tekesim that are at the core of Israeli collective memory and resilience are most often not attended by Palestinian Israelis, for the past 19 years, the Israeli-Palestinian Bereaved Families Forum has held a joint memorial ceremony on that day. Here, bereaved families on both sides come together to remember those lost in the conflict. This ceremony has always been a hopeful snapshot of what it could mean for Israelis and Palestinians to grieve and to thrive together.

5. Too Much Meaning

Though meaning making is central to Jewish and Israeli resilience, there is such a thing as too much meaning. When every event is absorbed into a sacred or historical narrative, those narratives can tip into messianic, exclusionary, or apocalyptic forms. The very traditions that offer comfort can also be wielded to justify extremism. In the aftermath of October 7, including during the war with Iran, some voices have framed the moment in messianic terms, invoking end-of-days language or absolute metaphysical battles. History becomes destiny; politics collapses into theology. Even further, battles that are part of an epic struggle are not subject to the moral scrutiny reserved for “ordinary” wars. In this climate, meaning is abundant—but the meaning itself can be terrifyingly destructive.

Conclusion: Choice, Agency, and the Tune that Endures

Long after my son and his classmates sang “The Tune” at their graduation, it was not the chorus but the refrain that stayed with me: “I hope that this year, the tune will remain.” It captured, more clearly than any speech could, the fragile continuity that defines Israeli life today and our determination to hold onto an inner melody even when the sea is rough.

Resilience has carried Israelis through a long season of rupture. Yet if resilience is reduced to endurance, it risks hardening into numbness, isolation, or false confidence. For it to remain life-giving, it must be joined with self-scrutiny, moral imagination, and the courage to ask: What future are we surviving for?

Rabbi David Hartman, reflecting after the massacres at Sabra and Shatila in 1982, urged Israelis to orient not around Auschwitz—the grammar of trauma—but around Sinai—the covenantal summons to justice, responsibility, and equality. As he put it, “We will mourn forever because of Auschwitz; we will build a healthy new society because of Sinai.” Hartman’s distinction captures a vital truth: The work of rebuilding must move beyond memory to moral responsibility and creativity.

What I want for my son, my daughter, and all Israeli children is not the armor of certainty but the flexibility to remain human in the most difficult circumstances; not a story that explains everything, but a covenant that obligates them to people and ideas beyond themselves. I want a resilience that does not close the heart, a patriotism that does not narrow the circle, and a faith that does not confuse history with destiny.

I want to tell them: Be supple like a reed, not rigid like a cedar. The task of this generation is not to wait for calm waters but to learn the art of buoyancy—to be flexible, accountable, and attuned to the covenant that binds us to others.

If we, and they, can remember the tune—if we can choose Sinai, again and again—our resilience will become more than survival. It will become the quiet music of a society learning, still, how to be good.