We Have Sinned, We Have Transgressed, We Have Polarized

Alon Shalev

Alon Shalev is a Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, and a Research Associate at the Jonathan Sacks Institute at Bar Ilan University.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Hebrew in Ofakim (Fall 2025).

Jewish tradition has long warned of the dangers of strife. The Midrash teaches that even when Jews worship idols, they are protected if they remain united—but when division reigns, destruction follows (Genesis Rabbah 38). The rabbis compared discord to fire; and fire, once unleashed, always consumes more than its intended target (Numbers Rabbah 18). These warnings were not abstract. They grew out of historical experience: the near–annihilation of the tribe of Benjamin during the civil war after the outrage at Gibeah (Judg. 19–21); the splitting of the united kingdom a mere generation after the First Temple was built, followed by decades of warring that ultimately enabled foreign conquest and expulsion; and, most famously, the destruction of the Second Temple followed by 2000 years of exile, which the Talmud attributes to sinat chinam, baseless hatred (bYoma 9b). For Jews, unity has always been more than a virtue; it has been a condition of survival.

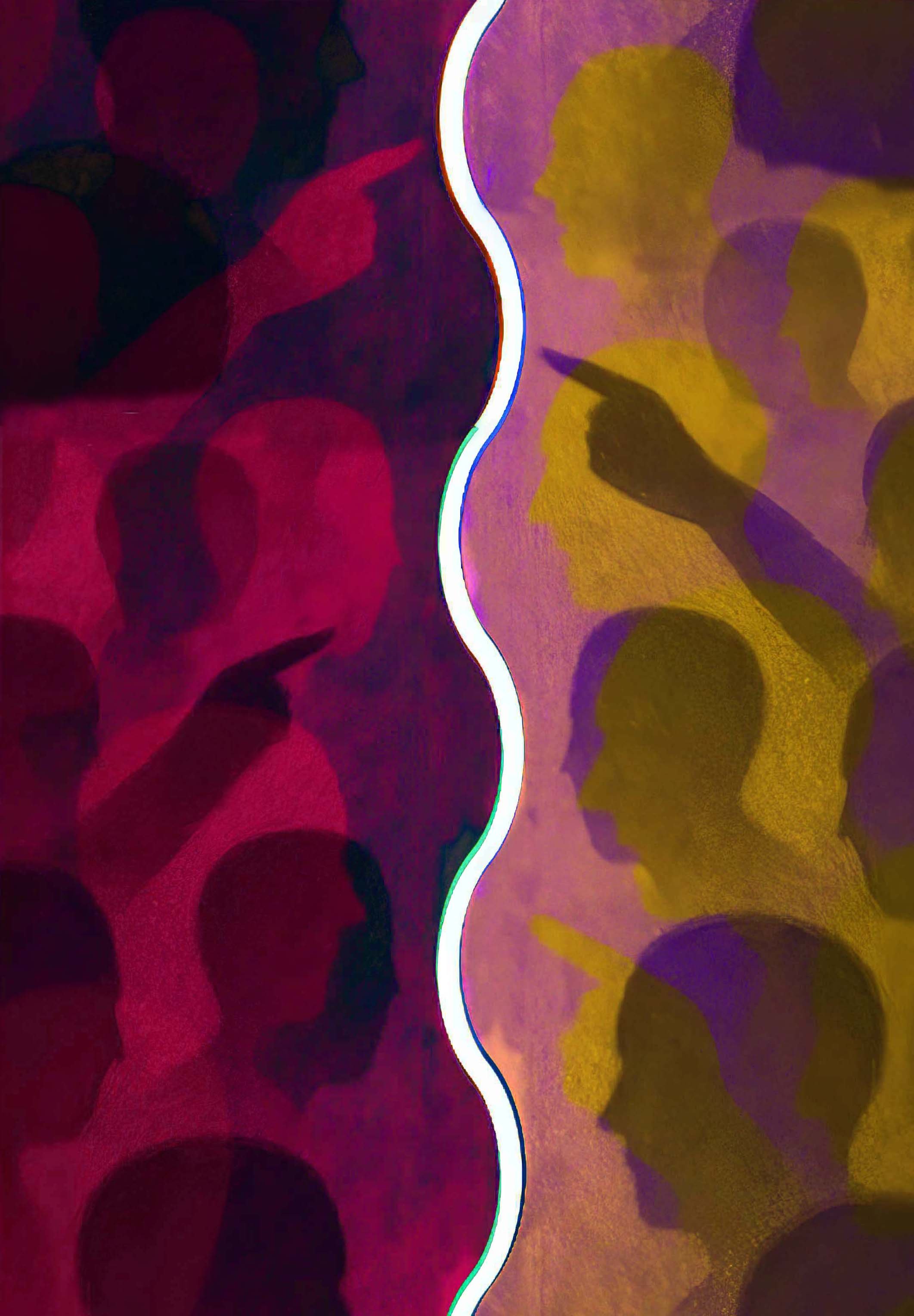

Today, this wisdom feels newly urgent. In the United States (and to a lesser extent in Canada), as in Israel, public life is corroded by polarization. Disagreement is no longer a matter of argument but of suspicion, contempt, and mutual delegitimization. Citizens do not merely dispute policies; they doubt one another’s good faith and even their right to belong. The civic fabric that sustains democracy is fraying, and for Jews—a people that has relied on solidarity both internally and in its relations with wider society—the danger is acute. The question we face is not whether we will continue to disagree; disagreement is inevitable and even necessary. The question is whether we can still regard one another as part of a fellowship, bound by ties that run deeper than our disputes.

Yet in some quarters, even the very language of unity is contested. To speak of “unity,” these critics argue, is not an honest appeal to solidarity but a manipulative device. It disguises power: an attempt by one side to mute resistance while pursuing its own goals. Under this view, civic friendship is naïve at best and oppressive at worst, a front for silencing dissent. The cry becomes, in effect: “Don’t call me brother.” This objection is not without force. Appeals to unity can indeed mask domination. But without some basic sentiment of unity—not uniformity of values or beliefs, but a felt commitment to one another’s place in a shared life—democratic societies cannot endure. Furthermore, as I will show, the presumably sober and diligent “unmasking” of unity can be—and perhaps more often is—its own sinister device.

In this essay, I will argue the following: first, that polarization should be considered primarily in terms of its function of facilitating a shift in how we manage disputes—from compromise and fair competition toward domination; second, that this shift is powered by two enablers: the exception problem and a culture of suspicion; third, that by teaching us to suspect our own suspicion, Jewish moral wisdom, especially the Mussar tradition, offers a counter-discipline; and finally, that a modest ethic of civic unity—perhaps thin, but genuine—is vitally necessary if we are to sustain disagreement without rupture.

The uses of polarization

Writing on polarization tends to revolve around two questions. The first, ostensibly the most fundamental, is, What is polarization? We must define the phenomenon to understand it. The second question is, Why are we polarized? The assumption here is that if we understand the causes of polarization, we can seek ways to mitigate it. But I believe that framing and addressing these questions in this way obscures a crucial aspect of the issue.

People tend to adopt a definition of polarization based on attributes. They describe either ideological polarization, marked by the radicalization of positions and the widening of gaps between opposing viewpoints; affective polarization, marked by increasing hostility toward opposing groups; or social polarization, marked by a decline in interaction between groups and increased isolation. When we ask the question this way—with a focus on how the problem looks—we miss something essential. We do not ask about polarization merely out of intellectual curiosity. We ask because polarization is hurting us. The question is not theoretical but practical—even, in a sense, existential—born of a lived problem. To really understand a problem, we must address what it does, not merely what it is. To understand polarization, then, we must analyze it from the angle that makes it salient to us and that troubles us: its function. What is the function of polarization?

The function of polarization is to alter the patterns of political disputes.

When, within any given framework, different factions hold preferences or goals that may come into conflict with one another—the default position in politics—we must be ready to manage these disputes. There are three basic patterns of dispute management. At one extreme there is the ideal, compromise: the parties negotiate and seek a mutually acceptable agreement that causes each side a tolerable amount of damage and yields each side sufficient benefit. At the other end of the spectrum is war, in the literal sense: the use of weapons and violence to eliminate or subjugate opposing parties and impose the will of one upon all.

In the middle lies competition. More than a pattern, competition is a framework composed of stable, agreed–upon rules and regulations, designed to let rival factions attempt to outperform one another on agreed-upon terms while still recognizing one another as legitimate contenders. Liberal democratic institutions exist for precisely this reason: to ensure that disputes are resolved through fair contests rather than hostile struggles.

However, an additional pattern lurks between competition and war: domination. This is a form of dispute management that lacks mutual legitimization, seeks a definitive and irreversible resolution, and treats all means as fair, including subterfuge, cheating, and boundary–pushing—anything short of outright violence—to dominate political power. A form of political cold war, if you will.

Polarization shifts a society or group’s dispute management from a frame of compromise or competition to one of domination, which is destabilizing and dangerous. Domination erodes the very conditions that make peaceful politics possible. Once rivals no longer recognize one another as legitimate participants, grievances cannot find resolution and harden into resentment. The losing side begins to feel not merely outvoted but excluded, and trust in public institutions collapses; courts, legislatures, media, even elections are dismissed as incomplete or rigged. When people no longer believe that their aims can be secured through ordinary political channels, they look to extra-institutional means, escalating pressure and tactics. If this dynamic remains unchecked, the logic of rivalry converts into the logic of force, and societies drift toward open conflict and, in the extreme, war.

This brings us to the question of why we are polarized. This question seemingly assumes that polarization is an unnatural state, a deviation from the default human condition of being nonpolarized. But paying attention to what polarization does highlights a problem with this assumption.

Let us reconsider the function of polarization: I argue that polarization arises in the transition from dispute management within constraints and striving for symmetry (competition) to dispute management free of constraints and exploiting asymmetry (domination). At this point, the misconception should be apparent. Any agent—individual, group, faction—desires acutely that disputes be resolved in its favor, and the license to exercise domination serves this desire. We would all prefer to be free of constraints when pursuing our goals.

As a result, every citizen—that is, every person exercising political agency in a state, or everyone who identifies with a group—faces the constant temptation toward polarization. For polarization is license: license to exempt some current political dispute from the “conventional” rules—the civilized, fair, universal rules—and to take drastic, uncompromising measures in the pursuit of goals and values. The real question isn't, Why are we polarized?, but rather, Why would we not be polarized?

Polarization belongs to the same class of human vices as theft, lying, violence, and selfishness. We are not born free of these vices; rather, we overcome them through socialization and internalizing rules and norms, with the aid of inhibitors and deterrents that shore them up during moments of weakness. We must reject the temptation of polarization in the same way we reject these other vices. To succeed in this, we must understand how we succumb to this temptation and what might serve as a bulwark against it.

Exceptions and unmasking: the inner logic of polarization

What enables the lapse from competition to domination?

Liberal-democratic competition, as we know it, stands on two legs. The first is formal procedures, including free and fair elections, separation of powers, equal treatment before the law, due process, and freedom of expression. The second is a set of shared, internalized civic values or norms that undergird those procedures and make them livable—pluralism, tolerance, openness to persuasion, and the presumption that political rivals are legitimate participants in a common civic project. Together, these norms are meant to ensure that disputes can be managed without rupture.

We were all raised to believe in these procedures and values. Schools teach tolerance, civics celebrates pluralism, everyone swears allegiance. Yet in practice, these very norms are coming undone. People speak the language of openness while refusing to hear one another; they profess respect for pluralism while retreating into ideological enclaves; they extol tolerance while demonizing dissent. Americans increasingly avoid dating or marrying across political lines, families have learned to keep silent at holidays or avoid gathering altogether, and whole communities now treat disagreement not as a challenge but as contamination. This trend has not bypassed the Jewish community and has only sharpened since October 7. Across synagogues, schools, and campus groups, the space for disagreement has narrowed: dissent is read as disloyalty, and loyalty as moral blindness. Friends stop speaking, families tiptoe or split, and institutions police the boundaries of the sayable.

Citizens and political agents alike profess to be and, indeed, believe themselves loyal to the procedures and values of competition, yet their lived practices betray the erosion of precisely those norms. What is at play here? How can ethics so widely affirmed be so widely abandoned at the level of instinct and conduct?

There are two primary enablers of this dynamic. First is the exception problem. Liberal democracies rely on formal, content-neutral norms that govern how we disagree, not what we must (or must not) believe. But precisely because these norms are content-neutral, they cannot tell us in advance when a claim or actor falls so far outside the shared framework that ordinary rules no longer apply. Real exceptions exist—we intuit this when, for example, we declare that a militant ayatollah who seeks to end elections should not be empowered by these norms. Ideas like “defensive democracy” and the “paradox of tolerance” are attempts to name those rare moments when our system must be protected from those who would use its openness to destroy it.

The boundary, however, between a true exception and a merely detested opponent cannot be objectively fixed. This is where polarization finds its foothold. If I can persuade myself that the other side is not merely wrong but illegitimate, then abandoning the conventional rules is not betrayal, but fidelity—not a vice, but a virtue. Sometimes this is warranted; the American Civil War was fought over a moral rupture where ordinary compromise was impossible. At other times, as with McCarthyism, what appears to be justification is in fact rationalization—a moral disguise for domination.

The exception problem alone is not enough to explain polarization. Exceptions, by definition, are quite rare. Most opponents, most disputes, most policies, while potentially bad, do not obviously qualify as existential threats. Taken at face value, they still belong to the realm of reasonable, even if strong, disagreement. The exception problem creates the possibility of suspending the rules but does not confer plausibility. For that, a second enabler is needed: a way of reinterpreting the other side, so that what is not obviously an aberration can be recast as one.

The second enabler is suspicion: It provides the plausibility that the exception problem requires to suspend the rules. Suspicion is both psychological and moral—a way of seeing and a way of indicting—and it teaches us to treat the surface of a rival’s claims as a mask for a disqualifying intent. Ricœur called this the “hermeneutics of suspicion” and identified three thinkers whose ideas exemplified it: Marx read liberal rights as a veil for domination; Nietzsche claimed morality is a veil for will-to-power; and Freud theorized that consciousness is a veil for repressed impulse. Most of the reigning theories in the humanities and social sciences of our time are founded upon these stances.

Suspicion has migrated from theory into political reflex, becoming the modus operandi of contemporary political activism, animating a broad range of “critical” ideologies as well as various shades of anti-elitist populism, and fueling practices such as cancel culture and identity politics.

Suspicion now operates as a framework for permission. It supplies the logic by which rivals are not merely disagreed with but incessantly “unmasked”: their stated commitments are dismissed as cloaks for something darker. So strong is the presumption of suspicion that examination of what a rival actually says or does is bypassed altogether, forging ahead to immediate dismissal and condemnation; the fact of disagreement itself becomes sufficient “evidence” of bad faith. Once a rival is reclassified in this way, he may be treated as an exception—no longer a participant in competition, but its enemy—and ordinary restraints need not apply.

Do not trust yourself

If polarization is a standing temptation, and suspicion-cum-exception is its framework for permission, then resistance must begin with treating our own suspicion as suspect. And on this point, Jewish wisdom has something to contribute.

The hermeneutics of suspicion is not foreign to the Jewish tradition, in which it was embodied with particular force in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the form of the Mussar movement. But Mussar’s version of suspicion has a significant difference: Unlike the unmasking of today, the “masters” of the Mussar movement directed their criticism inward. They demanded that the individual suspect himself, his motives, and his justifications.

The Mussarists clearly saw through the dynamic whereby any justification might equally be a rationalization. When a person is led by her own ideological bias or interest, she will always be able to find an argument that justifies—indeed mandates—her actions. Intellectual acuity and erudition are powerless to free a person from his or her biases. Quite the contrary, the mind is a magnifier; the more intelligent, more educated, more articulate people are, the greater their capacity to rationalize. A person’s aptitude for critical thinking will not produce a genuine ethical assessment of his reality unless he is accustomed to turning it inward. Without self–criticism, criticism of others will yield only biased results, and judgment of self will yield only license: the license to escalate methods and loosen restraints. Thus, a cluster of negative behaviors and expressions of bad character—anger, tantrums, vandalism, disruption, silencing, alienation, law–breaking—may be laundered, bleached, and re–packaged as “disruption,” “un–niceness,” “resistance,” and the like, and hailed as ideals, heroic acts worthy of emulation.

True, the intractable problem remains: There are cases in which such behaviors are genuinely called for. On the flipside, the plea for moderation, a desire to give the benefit of the doubt, and faith in compromise may also serve as rationalizations for those who avert confrontation or are unwilling to recognize evils performed by their kinsmen or members of their in–group.

The fact that there is no fixed or objective standard by which to determine whether a given situation is truly an exception or a state of emergency, or whether such an assessment is a delusion (self–delusion included) or a pretext, is a horribly vexing moral challenge. But there is no way out of it. The Mussarists held that a person’s only recourse was to toil unceasingly for the betterment of his character and to engage in constant self–examination and soul–searching, in the hope that this would help him to overcome temptation and avoid failure as much as possible.

A small fable, endemic to the Mussar movement, offers a rule of thumb for dealing with this problem. According to the story, a yeshiva student who was forcibly conscripted into the service of the Tsar appealed to his rebbe with the following plea: The meat served as part of the meager rations given to soldiers was obviously unkosher, and he feared that he would not be able to subsist on the little kosher food he could find. Was it permissible for him to eat the meat? The rabbi replied that he was permitted to eat the meat, but that he should be careful not to suck the marrow from the bones. The moral of the fable is clear: A person who resorts to extreme measures out of a genuine lack of choice—as a last resort—should take no pleasure in it. If such measures are accompanied by enthusiasm, zeal, hatred, glee for battle, holy wrath, ideological euphoria, self–congratulation, or a sense of exaltation, rather than sorrow, heartbreak, and gloom, it is almost certain that temptation, rather than necessity, is at work.

Unity in the face of temptation

Across the West, the current political landscape is marked by sharp affective and social polarization, manifested in an inability to reach compromises and agreements, an escalation of means used in political and civil struggles, and a profound mistrust of adversaries, who are painted and perceived as mortal enemies.

This polarization represents the collapse of the liberal idea that certain conditions might ensure the stability and integrity of a democratic–pluralistic society—i.e., a society composed of individuals with different values, goals, and preferences, all of whom enjoy equal political standing. The liberal approach holds that the combination of agreed-upon rules and minimal, basic shared values is enough to ensure that individuals and groups will compete in an orderly and fair manner for the power to shape the state and its policies without descending into domineering power struggles or war. But just as the Torah and its study are not sufficient to guarantee upright behavior—since even they are subject to distortion and perversion, as the Mussarists taught us—so, too, liberal values and regulations are not sufficient to protect democratic societies from polarization and the descent into dangerous dispute management that follows. These two legs upon which competition is meant to stand prove too easy to topple. A third leg is required for the structure to be sufficiently stable—a further safeguard to ensure, to the extent possible, that a large majority of society will shore up this arrangement, even when it seems tempting and viable to abuse and exploit its loopholes for the purpose of escalating a political struggle.

The inability of the liberal idea to restrain people in the heat of power struggles and policy disputes becomes understandable in light of philosopher David Hume’s critique of reason-based morality. Like the Mussarists, Hume, too, believed that reason and ideas are powerless against forceful emotions, and that, given an emotional pull toward some goal, a person would either abandon her values or (more likely) find ways to rationalize her actions within the framework of those values. Political disputes are characterized by a very high level of emotional intensity—not only, or even primarily, in the context of interests and preferences, but also in the context of ideology and the pursuit of justice. The only thing, argued Hume, that can stand up to the power of emotion is a counter-emotion (hence his attempt to ground moral systems in sentiment). What sentiment could be relevant to our political predicament and serve as a pushback against the temptation of polarization, which always seeks to insinuate itself into our patterns of dispute? The answer is unity—a basic civic affection, the felt sense that one’s fellow citizens are not merely interchangeable occupants of the same political space, but co-members of a shared commonwealth.

The family is the most basic model of this kind of unity. It is indeed common for larger human collectives—nations, peoples, or ethnic groups—to think of themselves as “vast families.” In family settings, like any other social setting, there often exist multiple opinions, conflicting interests, and competing conceptions of justice. But the fundamental characteristic of familial relationships (at least when they are healthy) is that the desire to be together and care for the well–being of co–members is equal to, if not greater than, the desire of each member to achieve his or her individual goals.

In frameworks where members are bound to each other by mutual interests alone, with no further bond or affinity between them (say, a pure business partnership between corporations), a dispute that ends in the decisive victory of one side or the dissenters’ decision to remove themselves from the group would be perceived as total success for the winning party—a clean sweep. Thus, in a political setting devoid of unity, where one party declares that if the state promotes such and such a policy contrary to his values he will get up and leave, the other party will welcome it. When people lack basic feelings of kinship or fellowship toward their neighbors, it is all too easy for them to condemn each other; to convince themselves of each other’s wickedness, extremism, and deceitfulness; and to justify relentless battle until the other side is fully subdued and the “right” position has won the day. Anyone who desires such total realization of his goals has an interest in suppressing any sense of affinity that members of his political camp may feel toward their opponents.

In a family, on the other hand, an outcome in which any member is ejected or left miserable and frustrated is perceived as a serious failure for the “winning” party. Indeed, his loss outweighs his gain. Similarly, in a political setting where basic unity remains intact, rival parties would wish their opposition to get at least some of what they are asking for. Where unity holds, rival parties hope to find common ground and compromise, or, in lieu of compromise, at least to compete fairly.

Critics of unity allege that the purpose of such discourse is to silence criticism and dissent. The exact opposite is true. Unity is precisely what enables dissent. When coexistence is conditioned upon shared values, a shared conception of justice, or an agreement upon some vision, then dissent is a threat that must be suppressed; and at the same time, rival groups in society must fight for the power to define these shared values and impose them on the rest of society if they are to pursue their idea of happiness. Such coexistence is what our sages called contingent love, ahavah ha–teluyah ba–davar, which disintegrates once the thing it is contingent upon expires (Pirkei Avot 5:16). When society is contingent upon shared values, pluralism tears it apart. Unity functions precisely where there is no consensus, whether ideological, religious, political, or any other kind. It allows for the airing of differences, deep and honest disagreement, and healthy dispute management; and facilitates arrangements and compromises that maintain social stability, free of corrosive subterranean currents that constantly threaten to erupt.

Unity must be nurtured. Not for the sake of flattening or obliterating differences, but on the contrary, for the sake of sustaining differences and allowing their management without descending into domination and war. There will always be exceptions where a person is painfully forced to disregard feelings of affection and take drastic measures against extreme dissenters. We can never be sure that what seems to us an exception is really one, or whether we are succumbing to the temptation to see it as such. But those whose sense of unity is intact—for whom such exceptions are not opportunities but tragedies—are far less likely to fail this test.

The force most antithetical to unity is not hatred, alienation, indifference, or divergence. It is “justice”—or rather, the desire and temptation to realize my conception of justice without inhibition or compromise—that most strongly obstructs unity. Unity compels compromise, making room for my brothers and sisters. Those who abhor compromise demand: “Do not call me brother!” Those who seek to suppress unity out of suspicion of their rivals, thereby supposedly justifying the drastic measures they employ, would do well to heed the Mussarists and engage in some soul–searching. Each and every one of us must examine ourselves and ensure that our discourse, the tone of our speech, the style of our writing, and most importantly, our actions, do not weaken unity, Heaven forbid, but strengthen and promote it.