In the Image of God: Amiram Shamir’s Children’s Chapel

CLOSE READ

Rachel Federman

Rachel Federman is an art historian and curator. She is the author of the exhibition catalogues Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet (2019) and Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton (2022).

Several years ago, I reencountered a structure I had known well in my childhood: Amiram Shamir’s Children’s Chapel, at SAR Academy in the Bronx.[1] A quarter of a century had passed since I had last seen it; thus defamiliarized, this singular, cylindrical concrete space, with its striking spherical ark and deep-set slab glass windows, appeared surprisingly strange, and strangely beautiful. I approached it this time as an art historian and found in it not only a well of embodied memory, but also a snapshot of American Jewish concerns in the latter part of the 20th-century.

Fifty years after its completion, the Children’s Chapel—a walk-in sculpture with an elaborate visual program circling its exterior—tells a compelling story about the values that gave rise to an influential Modern Orthodox Hebrew day school and helped shape the beliefs and self-image of generations of American Jews. In the chapel, Shamir referenced the Torah, the Holocaust, Israel, and ancient and modern Hebrew in a style that is strikingly modern but draws on ancient techniques. This combination of past and present suggested to the chapel’s early inhabitants—many of us first or second-generation Americans descended from Holocaust survivors—a way to understand our place in the world. As a uniquely warm and intimate space, it was also a site of conspicuous comfort and a respite from the almost delirious freedom we experienced outside its curved walls.

*

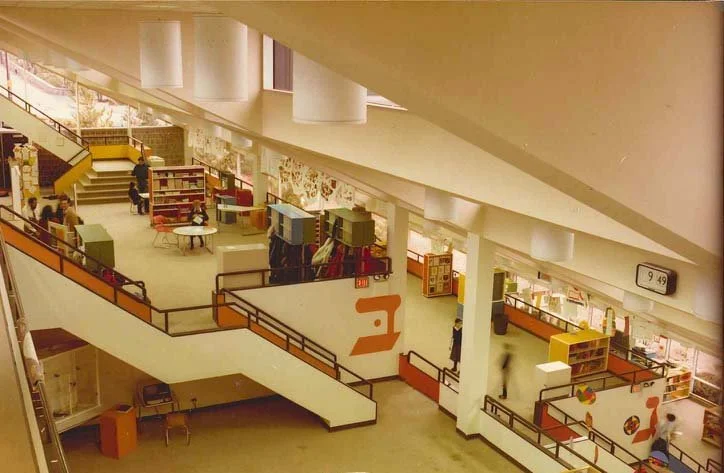

Between 1986 and 1994, I attended a school without walls. Designed by Charles Baskett of the Houston-based firm Caudill Rowlett Scott Associates, Salanter Akiba Riverdale (SAR) Academy was completed in 1974. Sited—not without controversy—on the former estate of the Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, the Jewish day school was part of the Open Education movement of the 1960s and 70s. Champions of open schools called for a more flexible, individualized, and child-centered approach to instruction. These ideas were realized architecturally in open classroom buildings like SAR and the Calhoun School in Manhattan. Built into a hill overlooking the Hudson River, SAR’s modern glass, steel, and concrete structure is composed of cantilevered terraces beneath a sloped roof. Inside, the four levels of the school are accessed by two sets of open stairs (fig. 1).

In 1975, New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger surveyed three open classroom schools, calling SAR “the finest overall.”[2] The school’s founding principal, Rabbi Sheldon Chwat, told Goldberger, “I was a little afraid we might have discipline problems with all this open space, but we don’t—the kids don’t have to buck the teachers since they feel free in this building to begin with.”

SAR was formed in 1969 through the merging of three existing Hebrew day schools in the Bronx. The brochure for the building campaign stated: “S/A/R Academy uniquely integrates the ongoing whole religious heritage of more than 4,000 years of Jewish faith and living with full openness and participation in the best life and style of our time.” This is a succinct encapsulation of the tenets of Modern Orthodoxy, as espoused by Rabbi Dr. Irving (Yitz) Greenberg, founding dean of SAR and a pulpit rabbi at nearby Riverdale Jewish Center. Advocating a holistic synthesis of traditional Judaism with modern secular learning and values, Greenberg is among the more progressive disciples of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, a pivotal figure in Modern Orthodoxy.

Speaking at the United Jewish Appeal National Conference in December 1974, three months after the doors of SAR Academy’s building opened, Greenberg warned that “Jews are not going to make it through this next period on momentum, inertia, sentiment, nostalgia, tradition, or even organization. Jews are going to have to be Biblical again.” He continued,

If we have the courage to walk, then a thousand years from now, our story will be a Bible; the holy days we create out of the Holocaust and the rebirth of Israel will be central Jewish holy days, even as we celebrate Exodus and Passover and Yom Kippur, our ancestors’ tradition. And this Bible will not just affect us; it will affect the entire world again. People will tell and study this story of the Jewish Bible of the twentieth century.

With the new school and other projects, Greenberg hoped to nurture “a Jewish identity vital enough to enable full participation in American society without assimilation or losing the primacy of Jewishness.”[3]

While the construction of an open-plan school building embraced “the best life and style of our time,” the school’s promotional literature also noted the plan’s similarity to the “spirit and model of the classic Beit Medrash of rabbinic study.” A school without walls to subdivide its interior—and with giant, brightly painted Hebrew letters, along with windowed views of trees, water, and sky throughout—was also an expression of freedom. When I attended, the three classes that comprised each grade occupied a single terrace, each class within view of the other. Stairwells and balustrades separated the terraces spatially, but there were no walls to prevent a student at one end of the building from hearing someone sneeze loudly at the other. As a fourth grader, I was devastated to be assigned to a teacher whose voluble admonitions I had grown accustomed to hearing as a younger student (she ended up being the best teacher I ever had). On the whole, however, we acclimated to the din and were not unduly distracted.

Many of SAR’s students were, like me, descended from Holocaust survivors who regularly sat at our dinner tables. At times, it felt that the school was as much for them as it was for us. Greenberg recently explained to me his view that the philosophy of open schools aligns with the Jewish tenet that every human being is created b’tselem Elokim (in the image of God). Greenberg wanted each child at the school to be treated with exquisite care and a concern to affirm his or her value and uniqueness, to draw into starkest relief the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust, in which Nazis burned Jewish babies alive to preserve Zyklon B, and threw children into death pits to save on bullets.[4] In Greenberg’s estimation, the “great religious act” of post-Holocaust Jewish life consisted in finding ways of “taking human beings whom we say are in the image of God and restoring that image… to absolute dignity.[5]

The chapel, a building within the building, was designed by Amiram Shamir, an Israeli artist who had settled in New York in 1969.The school has since undergone alterations, including the extension of the lobby through the enclosure of the exterior courtyard, but as I remember it, entering SAR was a choreography of expansion and contraction. The glass-walled entrance to the school stood at the north end of a large open courtyard with trees and benches. On a plinth at the west side of the courtyard stood Shamir’s fourteen-foot red-orange aluminum sculpture of the Hebrew letter aleph, which children were always climbing (fig. 2).

As in some of the best midcentury architecture, the courtyard, with red pavers underfoot, seemed to extend inside, to the tile-floored, glass-lined lobby. Shamir’s chapel, a white concrete and slab-glass cylinder, stood at the center of the pavilion (fig. 3). At the west end of the lobby, two sets of doors still open onto the vast, terraced classroom building, which is entered near its summit. An auditorium and cafeteria are located north and west of the lobby, putting the chapel at the center of the overall design. Chwat noted at the time the school opened that “the chapel is not only the center of the school physically, but psychologically and spiritually.”[6]

*

When I attended SAR, the chapel was used for prayer by the seventh and eighth grades; the younger students prayed in their classrooms. But it was nevertheless a familiar place to all of us, a site of special programs and unsupervised free play in the mornings. It was especially well-suited to games of tag and hide-and-seek. The cylindrical structure, which fit snugly within the lobby’s original dimensions, is entered from the west. The interior is structured like an amphitheater, with three rows of stepped benches curving around its edges (fig. 4). The back row on each side is separated by a half-wall and a curvilinear metal screen mechitzah, denoting the women’s section; in Orthodox tradition, boys and girls of Bar and Bat Mitzvah age sit apart during prayers.

The intention behind the circular plan was to enhance all students’ sense of inclusion. In notes from the time, Shamir wrote, “The concept of the circular space symbolizes evolution, infinity, and wholeness. It helps the student worshipping in the space to be a participant rather than an observer.” Shamir initially designed a mechitzah that was as unobtrusive as possible. The original screen partition was composed of thin metal wheels with filament spokes that were practically invisible. It was replaced after the original filaments were destroyed by the intrusions of countless small fingers, but the idea of a porous barrier was reproduced in a more durable material.

With its intimate scale and mauve-pink carpet covering benches and floors alike, the chapel felt less like a shul than a conversation pit, a popular design feature of the 60s and 70s. In contrast to the open, rectilinear main building to which it responds, it is embracing, intimate, even womblike—a sanctuary in more ways than one. A large, square wooden table with a carpeted plus-shaped base occupies the center of the room. This is where the chazan, the prayer leader, stands.

The focal point, however, is the aron kodesh, the holy ark containing the Torah at the east end of the room. A sculpture in the round formed from concrete, the ark is a spherical section resting on a trapezoidal base. Although it evokes contemporaneous Space Age designs, it is distinguished from that sleek trend by its organic edges and textured surface. The doors are fitted into a round-edged rectangular aperture in the center of the orb. They are covered in an ornate textile skin with fluid, petal or flame-like forms in shades of pink and red. The Hebrew word halleluyah is spelled out in white stylized letters and further embellished with clusters of white and translucent beads. The fiber artist and feminist scholar Ita Aber worked six months of eight-hour days to complete the 116,000 stitches of Shamir’s design for the ark doors.[7] The back side of the ark forms part of the exterior wall, framed by glass and concrete panels constructed by Shamir in sections. Textured slab glass in red, orange, yellow, blue, and lavender hues evoke the burning bush in which God revealed himself to Moses in the book of Exodus.

Shamir’s approach to materials was similar to the school’s philosophy; he sought to synthesize new forms with ancient traditions, noting that the glass he used “possesses the same qualities found in medieval glass.”[8] (In the same vein, his favored medium for painting was egg tempera on wood.) If there was any incongruity in this approach, I was unaware of it. Just as early and constant exposure to an open plan school building inured many of us to distraction, so too were we inducted into a world where the old and the new sat comfortably side-by-side.

Shamir’s work shows the influence of several important modernist figures, chief among them the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. In Le Corbusier’s Chapel of Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France (1955), light enters through scattered stained-glass windows, while additional light flows to the interior from a gap between the top of the walls and the roof; Shamir similarly stopped his circular wall just short of the lobby’s ceiling. Le Corbusier was a leading figure of the International Style in architecture, which deeply influenced the architecture of Tel Aviv, where Shamir grew up.

The International Style influenced the design of many mid-century Jewish buildings besides SAR. In the postwar period, leading synagogue designers in the United States, such as Percival Goodman and Erich Mendelsohn, adapted the language of modernism to their own inventive ends, often incorporating modern art into their plans.[9] Like them, Shamir possessed a sophisticated awareness of modernist tenets, but went beyond them. This is especially apparent in his embrace of applied ornament, decoration that is supplemental to the structural needs of a building. The exterior of the Children’s Chapel alternates between clean expanses of unadorned concrete and areas of relief formed by groupings of cast concrete panels. The panels, which feature abstract designs, recognizable images, and language in relief and intaglio, come together like pieces of an ill-fitting puzzle. The visual iconography is one Shamir had begun to develop in Israel more than a decade earlier as an art advisor to the City of Tel Aviv and a member of a cohort of creatives that included such luminaries as the songwriter Naomi Shemer.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

The Children's Chapel includes numerous circular forms, beginning with the room itself and its orienting ark. Wheels formed the original mechitzah, described above, and part of the ner tamid (eternal flame), suspended near the ark. Individual wrought iron wheels project from the exterior wall, and the shape is evoked in a cast panel featuring representations of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The wheel suggests progress and continuity, but Shamir’s circles are at times broken or otherwise imperfect, pointing to his skepticism of closed systems and myths of perfection.[10]

The frequent appearance of wheels, gears, cogs, and other mechanical imagery in Shamir’s work points to the influence of the Bauhaus and the geometric language of International Constructivism, to which Shamir was indebted. But geometry was only a point of origin for Shamir, who used it to develop a personal, rather than a broadly universal, language of expression. His daughter, architectural historian Adi Shamir-Baron, suggests that the wheel is also, among other things, an emblem of Shamir’s sympathy for and identification with the laboring class. He elevated work to a spiritual level, once saying, “Without sounding too romantic I have to say that for me work is a form of prayer.”[11] Shamir not only designed his work; he also fabricated and installed it, collaborating closely with tradesmen on elements he could not execute himself, such as the wrought iron grille that climbs the exterior wall in an evocation of Jacob’s ladder (fig. 5).

Peter Giuliano was a young man-with-a-van when he met Shamir in the early 1970s and worked with him on the Children’s Chapel and other projects. The two men fabricated the concrete panels and slab-glass windows in Shamir’s studio in Manhattan’s Garment District, later hauling them down a flight of stairs to the elevator and transporting them to Riverdale. Giuliano remembers the laborious process of creating and casting the panels, which were affixed to the exterior walls of the chapel with threaded rods. Shamir developed a concrete formula that incorporated fine white sand and excluded rocks to achieve a supple, whitewashed aesthetic (the chapel has since been covered with white paint). Inside the individual molds, Shamir applied layers of Plastalina clay into which he carved in negative the texts and intricate patterns that would later be cast as positives in concrete. When I spoke with him about the experience nearly fifty years later, Giuliano was still moved by Shamir’s intense, even excessive, attention to the details and execution of his art. Shamir summarized his approach in a fragmentary quote recorded by a journalist in 1990: “the ethic in the aesthetic,” he said, “the power of creativity, the desire of man to grow wings to get closer to the big light.”[12]

The menorah, the seven-branched lamp that illuminated the ancient Temple, features prominently in the iconographic program of the chapel. Its contours are repeated and abstracted in the shapes of individual concrete panels, lending visual consistency to this architecture of fragments. On the exterior south-facing wall of the chapel, panels containing thick pieces of glass—some etched with the hand-shaped hamsa (an amulet for warding off the evil eye) and others arranged in abstract or figurative patterns—coalesce triumphantly into the shape of a large menorah (fig. 6). Toward its center, in place of a flame, is the Hebrew word hallel, referring to the prayer of praise recited on holidays. The central column of the menorah is formed from a stack of the first four letters of the Hebrew alphabet: aleph, bet, gimmel, and daled. Three panels along the southwestern side of the chapel exterior bear Latin, Old Greek, Hebrew, and paleo-Hebrew letters. The prominent placement of the letters in the chapel program, and elsewhere inside and outside the building, underscores the central role of the Hebrew language in the pedagogical program of the new school.

Extending west from the menorah’s left edge are the words mitzion michlal yofi, Elohim hofiya, a phrase from Psalms that extols Jerusalem, here called Zion, as the place of perfect beauty from which God emanates. The concrete and slab-glass menorah originally faced the lobby’s glass curtain wall, oriented slightly eastward, toward the doors, for maximum visibility.

A very different iconographic and textual program occupies the opposite side of the structure (fig. 7). Amid a cluster of panels along the northeast section of the exterior wall appear two luchot (tablets), like those Moses brought down from Sinai. Notably, they are not inscribed with the ten commandments. Instead, the righthand tablet, which is broken in two, bears the names, in English, of eleven Nazi labor and extermination camps. Inscribed on the lefthand tablet is the traditional blessing one makes upon learning of a death, baruch dayan emet (blessed is the true judge). Raised letters on panels beneath these somber tablets bear the words El maleh rachamim (God full of mercy), from the dirge for the departed, and further to the left, yitgadal ve-yitkadash, the first words of the mourner’s Kaddish. Although the chapel is not a Holocaust memorial per se, the inclusion of this element follows a pattern that developed in the postwar period of locating small memorials to the Holocaust in synagogues.[13]

Between these extremities of Jewish liturgy—celebration and mourning—stands the rear of the ark (see fig. 3). It is adorned with cast panels, iron wheels, and, in high relief, a broken sphere containing machine parts. The base of the structure appears to comprise two abstracted figures, one in intaglio, the other in relief. Considering Shamir’s attraction to angels as a subject, I read the incised arcs that extend from either side of the figures as wings, but I think the imagery is purposefully ambiguous.

Both Shamir and Greenberg had been transformed by the Eichmann trial, which took place in Jerusalem in 1961. Shamir said, “We were in Tel Aviv then designing the Industry in the Kibbutzim Fairground Pavilion and the trial aired from Jerusalem on the radio. The trial left an indelible impression on a lot of us, it single-handedly changed things. Before, we Israelis didn’t want to think about the war, we were embarrassed …. We were a macho culture. We had been taught to fight, the spirit was one of strength, youth, invention, bravery, arrogance.” But, he continued, the experience of listening to the witnesses—one in particular—inspired in him a “great wave of identification with those sacrificed.”[14]

In 1961, Greenberg was on a Fulbright scholarship, teaching American intellectual history at Tel Aviv University. Although he declined an invitation to attend the trial, he later wrote, “Within a couple of weeks I became totally caught up in the Shoah, spending most of my time at Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial Authority in Jerusalem.” Greenberg struggled to reconcile “the depth of horror that I relived all day and the return home, seeing Jerusalem bursting with life,” as if the “the covenant was being fulfilled before my eyes.”[15] The seemingly irreconcilable duality of the Holocaust and the thriving State of Israel henceforth became a major theme in Greenberg’s theology, leading him to posit a “dialectical faith.”[16]

During the years between 1965 and 1972, when Greenberg was rabbi at the Riverdale Jewish Center, he began to articulate the idea, which would later appear in his writings, that the Holocaust, which he called “ the most radical challenge to Jewish belief and faith that ever took place,”[17] represented a shattering of God’s covenant with the Jewish people: “Since there can be no covenant without the covenant people, the fundamental existence of Jews and Judaism is thrown into question by this genocide.”[18] (This radical proposition is tempered somewhat by Greenberg’s situation of the breach within a historical process of divine withdrawal in the service of enabling human autonomy.[19])

Shamir’s fractured tablet, inscribed with the names of death camps, is an illustration of Greenberg’s view that the covenant had been broken, while the south-facing façade—and the founding of SAR itself—embraced Greenberg’s concept of a “voluntary covenant,” that the Jewish people would choose to continue their relationship with God.

As an Israeli-born artist who had recently immigrated to the United States, Shamir himself embodied the continuity of the Jewish people, which Greenberg witnessed firsthand in Jerusalem. By all accounts, Shamir was an exceptionally charismatic and vibrant figure. That he was not a traditionally observant Jew did not detract from the significance of his Israeli background for Greenberg. In 1974, Greenberg offered a view of secular Israelis: “We have to understand the fundamental reality of Israeli life in which a so-called secular Israeli gives his life—stakes his life that the people of God will survive; without such a people there can be no faith in God, no belief, no Torah.”[20]

Shamir-Baron explains that her father’s art was itself an expression of his spirituality: “He emphasized the role of the artist and of the work of art as a meaningful, unmediated expression of the dialogical impulse in Martin Buber’s Ich und Du [I and Thou] principle. In other words, he was devoted to the practice of communicating with the divine (divine self) through the art, as the art.”

*

The personal transformations experienced by Greenberg and Shamir in 1961 were part of a broader shift in communal perceptions of the Holocaust in Israel and America. While, according to historian Hasia Diner, American Jews did mourn the Holocaust during the 1940s and ’50s in a variety of ways, the 1960s marked the beginning of the large-scale efforts to memorialize the Holocaust that shape the Jewish landscape today.[21]

Greenberg played a prominent role in this shift. As co-founder of the National Jewish Conference Center (later renamed CLAL, National Jewish Center for Jewish Learning and Leadership) in 1974, Greenberg initiated Zachor, the Holocaust Resource Center, lecturing widely and organizing conferences on such subjects as the children of survivors. In his forceful response to Robert Alter’s critique that “our existence is warped by being viewed in the dark glass of the Holocaust,” Greenberg writes, “I prefer the current condition… to the decades of indifference, silence, and even shunning of survivors which preceded it. The surge of interest in the Holocaust is part of a delayed reaction to a religious and cultural earthquake—one which is still denied and evaded by millions.”[22] In 1979, Greenberg was appointed executive director of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, which culminated in the opening of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. in 1993.

Shamir, too, was deeply involved in efforts to promote Holocaust remembrance. In 1970, he designed a poster for the World Federation of the Bergen Belsen Survivors commemorating 25 years since the liberation of the camp. In Yiddish, Hebrew, and English, it declares, “Remember,” with the dates 1945-1970, and “25 Years Later: Never Again!” The names of death camps, written in English, are interspersed with the traditional opening words of the Kaddish.[23] In 1974, Shamir constructed his first of more than two dozen Holocaust memorials, a wall at the Jewish Center of Bayside Oaks in Queens. The memorial he designed for the Jewish Center of Southern Arizona in Tucson in 1990, was at the time the largest Holocaust memorial in America. Like the Children’s Chapel, the Tucson memorial features a set of tablets, though these appear to have toppled over into a reflecting pool. They are inscribed with the names of over a hundred camps, including all those in which local survivors in Tucson had been imprisoned.

In a newspaper profile published at the time, Shamir appears to echo Greenberg’s teachings, stating, “These tablets are broken tablets. This is the law broken.” Noting the resemblance of certain elements in the Tucson monument to Shamir’s earlier Holocaust memorials in his book The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, art historian James E. Young observes, “By rearranging a number of repeating elements from his previous work, the artist might even be said to have created a kind of modular monument, eminently adaptable to its new surroundings.”[24] The construction of the Children’s Chapel at SAR was a key stage in Shamir’s articulation of this modular, yet highly expressive, visual language.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened on April 22, 1993. With its dedication ceremony presided over by President Bill Clinton, it solidified Holocaust remembrance as not only a Jewish, but a national, priority. In the spring of 1994, my eighth-grade class visited the museum during an overnight trip to Washington, D.C., the first SAR group to see it. At the time, the memorial museum, and the messages it conveyed, seemed familiar to me, as though they had always existed. Writing this essay has helped me to understand why. The more I looked at Shamir’s iconographic program and considered it in relation to Greenberg’s writings and activities, the more I came to recognize the scale of Shamir’s compact aesthetic statement. It encompasses a worldview which was nascent in its time, but which became, within twenty years, the dominant lens through which many American Jews understood, and continue to understand, themselves.

My education was intricately entangled with this historicizing process. But there is something else. Reencountering Shamir’s chapel, I was astounded by its beauty, strangeness, consistency of vision, and also by the unusual level of care that went into it, which Giuliano observed during its construction. When I think back on my lived experience of the chapel, what resonates most is its sense of affirmation: that each child who encounters it, and sits within its embracing walls, is worthy of the care, attention, and artistry that Shamir poured into it.

Endnotes

[1] I am extremely grateful to Adi Shamir-Baron for guiding my understanding of the work of her father, the artist Amiram Hadar Shamir (1932-2007). My sincere thanks to Julia Elsky, who read an early draft of this essay and made astute suggestions for further reading.

[2] Paul Goldberger, “School Design Reflects Education Shifts,” New York Times, September 17, 1975. The building also received the top Bard Award for excellence in New York architecture.

[3] Irving Greenberg, “Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: A Retrospective View,” in Adam Ferziger, Miri Freud-Kandel, and Steven Bayme, eds., Yitz Greenberg and Modern Orthodoxy: The Road Not Taken (Boston, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2019), 38.

[4] Irving Greenberg, “Cloud of Smoke, Pillar of Fire: Judaism, Christianity and Modernity after the Holocaust,” in Auschwitz: Beginning of a New Era? Reflections on the Holocaust, ed. Eva Fleischner (New York: KTAV, 1977), 9-10, 15.

[5] Irving Greenberg, “Confronting the Holocaust and Israel,” An address to participants in the 1975 UJA Study Conference, 16. http://www.rabbiirvinggreenberg.com/lecture/confronting-the-holocaust-and-israel/

[6] Thomas Flynn, “Riverdale School Blends Old, New,” The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, NY), June 3, 1974.

[7] Aber writes that Shamir “permitted me to interpret his design in the manner in which I saw fit.” Ita Aber, The Art of Judaic Needlework: Traditional and Contemporary Designs (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979), 48.

[8] Quoted in Adi Shamir-Baron, ed., Amiram Shamir: The Art of Work (unpublished book prospectus), 19.

[9] Janay Jadine Wong, “Synagogue Art of the 1950s: A New Context for Abstraction,” Art Journal, Vol. 53, No. 4, Sculpture in Postwar Europe and America, 1945-59 (Winter 1994): 37. See also Lance J. Sussman, “The Suburbanization of American Judaism as Reflected in Synagogue Building and Architecture, 1945-1975,” American Jewish History, Vol. 75, No. 1 (September 1985): 31-47.

[10] Adi Shamir-Baron and Pamela Sharon, conversation with the author, November 8, 2022.

[11] Quoted in Shamir-Baron, ed., Amiram Shamir, 17.

[12] Quoted in Peter Ember, “Images in Light,” The Journal News (White Plains, NY), June 10, 1990.

[13] Hasia Diner, We Remember With Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945-1962 (New York: NYU Press, 2010), 37.

[14] Quoted in Shamir-Baron, Amiram Shamir, 8-9.

[15] Irving Greenberg, “Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: A Retrospective View,” 15-16.

[16] Greenberg, “Cloud of Smoke, Pillar of Fire: Judaism, Christianity and Modernity after the Holocaust,” 27.

[17] Greenberg, “Crossroads of Destiny,” 13.

[18] Greenberg, “Cloud of Smoke, Pillar of Fire,” 8.

[19] Irving Greenberg, For the Sake of Heaven and Earth: The New Encounter between Judaism and Christianity (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2004), 81.

[20] Greenberg, “Crossroads of Destiny,” 19.

[21] Diner, 365-390. See also Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999).

[22] Robert Alter, “Deformations of the Holocaust,” Commentary, Vol. 71, No. 2 (Feb. 1981), https://www.commentary.org/articles/robert-alter-2/deformations-of-the-holocaust/. Irving Greenberg, “Letters from Readers,” Commentary, Vol. 71, No. 6 (June 1981), https://www.commentary.org/articles/reader-letters/the-holocaust-5/.

[23]The poster is reproduced in Gary Yanker, Prop Art: Over 1000 Contemporary Political Posters (New York: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd., 1972), p. 241, no. 998. Shamir’s name is given incorrectly as “S. Hamir.”

[24] James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 301.